Flight training when even the experienced aren't that experienced

Learning to fly in the First World War was often more harrowing — and more deadly — than combat

It’s easy to imagine how someone learns to fly in the 21st century. You enrol at a long-established flight school that has a curriculum developed and refined over many decades. Or you enter a similarly structured program in the military. You may end up flying commercial planes, private jets, helicopters, fighter aircraft, smaller props, whatever. No matter how it ends, the process of becoming a pilot is clear, and there is little doubt about the effectiveness of the training.

Now imagine that no one — not even your most experienced instructor — has more than a decade of experience. And hardly anyone at all knows what it’s like to shoot at or fight another plane in the air. That’s where the Royal Flying Corps and other air forces found themselves when the First World War started in 1914.

The RFC was training some pilots before the war started at the Central Flying School, which had been set up in 1912. Generally the flight training program took six months, and taught the basics of aeronautical physics (still poorly understood at the time), how to take off and land, a bit of navigation (which was mainly about map-reading, identifying landmarks and using a hand-held compass, as there were few if any instruments in the plane), and not much else.

If it wasn’t already obvious how dangerous flying a plane was at the time, consider the fact that in one six-month period before the war started, there were three fatal accidents at the school.

As soon as hostilities erupted, the demand for pilots soared. But the Central Flying School was small and had not been well-funded, since up to this point it wasn’t even yet clear what role airplanes would play in a war. Immediately, military leaders ordered the setting up of air fields and training academies in as many places as possible across Britain. But expansion wasn’t easy. The Central Flying School already employed pretty much everyone who was considered an “expert” in flying. Some civilian pilots had to be brought on board to help.

In an act that can only be described as desperation, the school cut its already rudimentary pilot training program down to three months from six, so that it could move twice as many men through it at a time.

On the one hand it’s understandable why this was done. The army realized early on that airplanes would be an amazing reconnaissance tool. Flying over enemy territory and seeing trench networks, troop movements, locations of barracks, all this was incredibly useful information. And the Germans were doing it too, so both sides needed to keep up. It would have been easy to conclude that the success of the war effort depended on the number of pilots available.

Of course it wasn’t long before planes also started fighting one another in the air, first by shooting at one another with handheld rifles. But that game got more sophisticated in a hurry, and tactical dogfighting soon became a thing. Men had to be trained to do this.

This program of hardly training pilots at all continued for more than a year, until early 1916. It came with consequences that were hard to swallow. By some estimates, more pilots were dying in training accidents than in combat. At that rate, the total number of pilots available would start going down, not up.

The man in charge had had enough. The commander of the RFC, Major-General Hugh Trenchard, repeatedly complained that too many men were too poorly trained. He ordered improvements. In March, 1916, pilots would have to meet new qualifications in order to be certified:

Fifteen hours of solo flying

Made at least one cross-country flight of 60 miles or more, during which he must land somewhere other than an established airfield

Technical tests that include flying to 6,000 feet, shutting the engine down, then landing on a bullseye that is 50 feet in diameter

Land in the dark where the runways is lit by flares

Pilots were also forced to fly in bad weather more often, and learned how to drop bombs and fight in the air. In late 1916, the qualifications were made more strict, by requiring some pilots to have twenty-eight hours of solo flying time before getting their wings.

By the time John Buckland Richardson, my great-grandfather, entered the Royal Flying Corps in September of 1917, everything had changed. Now, training programs were eleven months long, and included intensive courses at the School of Military Aeronautics in Reading or Oxford.

The exact details of his training aren’t known, but a family story seems to confirm his completion of the cross-country flight requirement.

In what was probably the spring or summer of 1918, Richardson flew a small plane, with an RFC instructor on board, to a farm in Lincolnshire, somewhere near the town of Grantham. This was about 100 miles away from Oxford, where the flight likely started.

The farm belonged to relatives of Richardson’s mother, the Burtts. After landing on the property, he and his instructor were greeted by the family and ate lunch with them at their house. They may have made a second takeoff and landing at the property to fulfil the training requirement, then they took off again and headed back to Reading.

My grandmother (Richardson’s daughter) always told this story with a sense of outrage in her voice. She considered it audacious, rude, and entirely inappropriate for her father to have made that flight to the family farm. She saw it as a prank. A case of absconding from his military duties to go on a cross-country joy ride. She also assumed the family was shocked and angry when they saw their young relative do something as outrageous as land his plane on their farm.

But in fact, he was probably fulfilling one of the key requirements of becoming a pilot. He needed to fly a considerably distance across the country, and land somewhere that was not an airfield. Why not go to the family farm? It’s not known if the Burtt family had advance notice he was coming. Probably they didn’t, as telephones weren’t around much yet and the flight would have likely been made on short notice, making it impossible to send a letter ahead of time. But so what? It’s hard to imagine them being unhappy to see the young man earning his wings, doing his part for the war effort, and still only 18 years old. They were probably delighted to serve him and his instructor a meal.

So much change in so little time

In earning his wings, which he did in August, 1918, Richardson learned not just how to fly, but how to maintain and fix airplanes, how to navigate, do reconnaissance, take aerial photographs, how to shoot the enemy from the air, make tactical manoeuvres, drop bombs, fly at night, fly in formation, avoid anti-aircraft fire coming from the ground. This, in addition to tangential subjects that would come in handy, such as what to do when captured by the enemy.

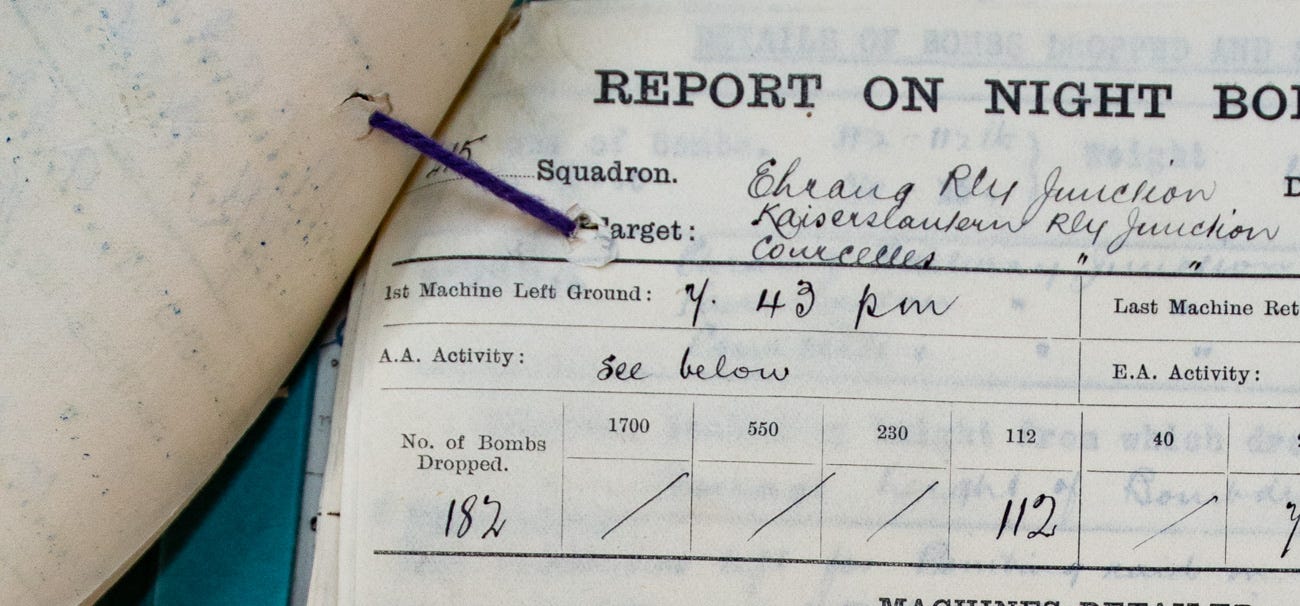

Within weeks of becoming a certified pilot, Richardson was sent to France as part of the Independent Force. He became part of 215 Squadron, a night-bombing unit that was part of a wider effort to bomb German targets 24/7. You can read what happened to him on his first ever combat flight here:

The night that changed three RAF airmen forever (part one)

Every life is defined by pivotal moments. Crucial events that shape who a person is, change the course of their existence, transform them into the character they later become.

Richardson and other pilots at that time were far better equipped to deal with what faced them than they would have been in 1915 or even 1916.

We talk in the 21st century of how fast the rate of progress and change is in society. But consider for a moment just how fast the technology of airplanes, and the skill of pilots, changed in the war. In 1914, men got a few months of training and were flying around in tiny planes with extremely limited range that could only operate in daylight, in good weather, and at low altitudes. Bombs were too heavy to carry and guns weren’t even attached to the planes.

Four years later, pilots were going through intensive training that lasted close to a year, and were flying aircraft many times the size, weight, speed and power, some with multiple engines. They could fly far higher than anyone imagined just a few years earlier. They were also flying in formation, carrying up to 2,000 lb of bombs that could cause previously unknown levels of destruction. As the war came to the end, planes were in development that could fly non-stop from London to Berlin and back again, a round trip distance of more than 1,000 miles. Anyone suggesting at the start of the war that a plane could one day do that would have been laughed out of the room.