The night that changed three RAF airmen forever (part one)

More than a century after it happened, the story of one night can be brought to life in extraordinary detail

Every life is defined by pivotal moments. Crucial events that shape who a person is, change the course of their existence, transform them into the character they later become. It’s usually easier to recognize these moments when looking back rather than as they happen. Am I currently in the middle of a life-changing experience? Hard to say, easy to dismiss.

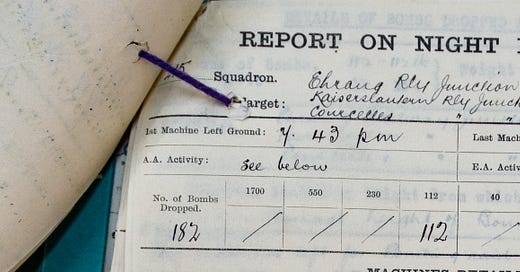

Whether it was obvious at the time or not, it’s clear that one of these defining moments happened for three airmen on the evening of Saturday 14 September, 1918, and the night that followed. They belonged to a squadron that was part of the Independent Force, an arm of the RAF that conducted bomb raids on Germany. The Force ran its operations out of aerodromes in Nancy, France and the surrounding area. (I will have more to say about the Independent Force in the weeks and months ahead.)

The intention was to run bombing raids 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, but weather sometimes prevented that. In the first few weeks of September, the region was hit with strong winds, low cloud and lots of rain. Visibility was usually poor. Terrible weather for flying. Some days the weather was so bad, all planes were grounded.

As the middle of the month approached though, the weather improved enough to allow bombing missions to resume, even though conditions were described as “fair” and it was still raining on Friday at the aerodrome in Xaffévillers, not far from Nancy.

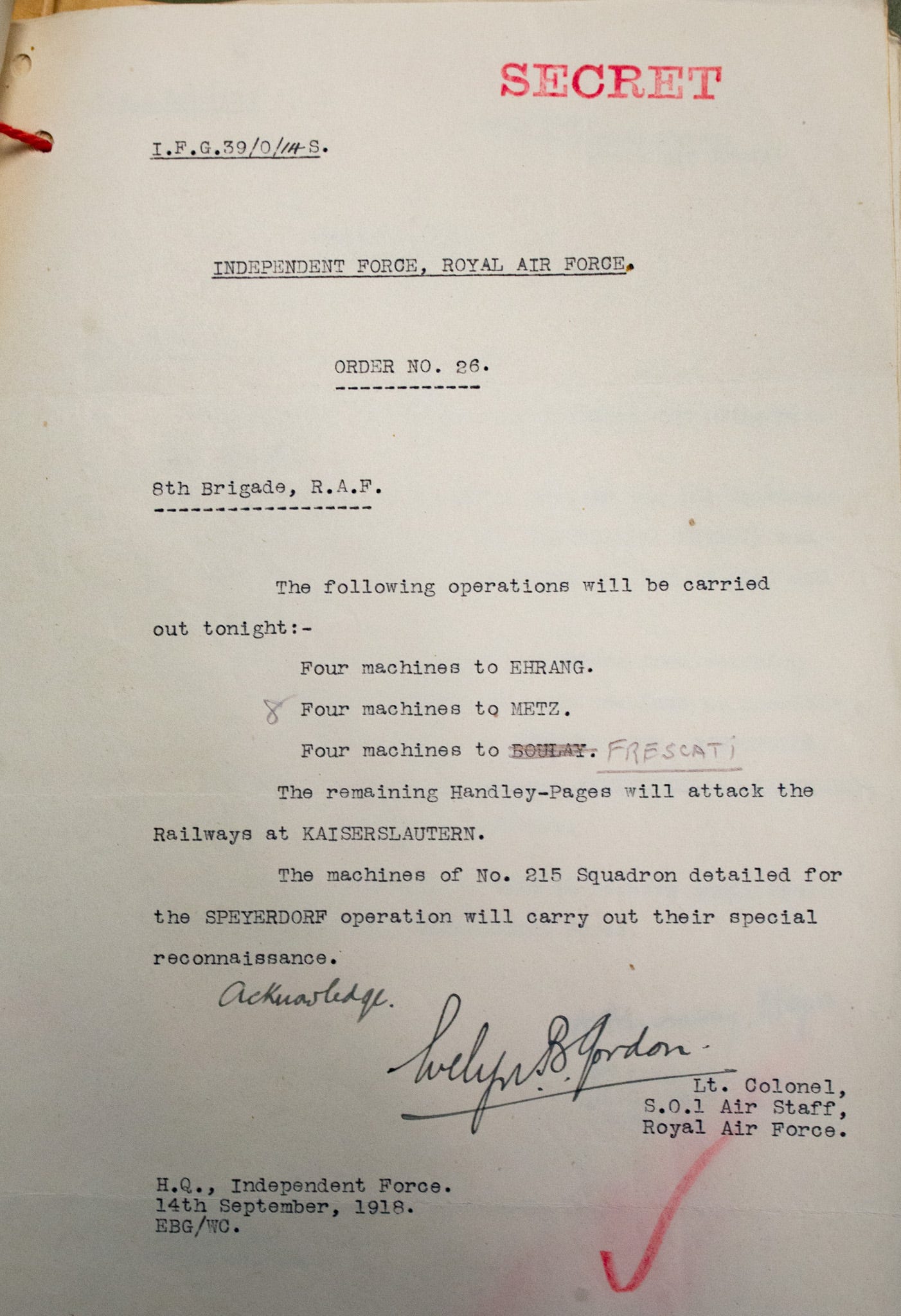

Secret orders came from headquarters of the Independent Force on the 14th, probably in the morning. They listed the targets the heavy bombers were to hit on that day.

The document above is chilling to look at. The red SECRET stamp at the top would have been placed on any document that laid out details of a future operation. In this case, only hours in the future. At the time it was typed, this would have been highly sensitive information of a coming attack, and obviously not something you’d want to fall into the wrong hands. It orders the planes to strike various targets in Germany starting that evening, the 14th of September.

Orders such as this were made countless times during the war, making it tempting to gloss over them as routine, even mundane. Another night, another bomb raid.

But when I look at this yellowing piece of paper with the typed words and the red stamp and the Lt. Colonel’s signature, I get physically cold. These are not just documents. They are the ghosts of those who flew and fought. The significance of it weighs me down, paralyzes me briefly. I am watching the lives of men being transformed in real time.

Would they have seen the notorious trenches far below? Probably, because they’d be looking for them. Once over enemy territory, they knew what was waiting for them.

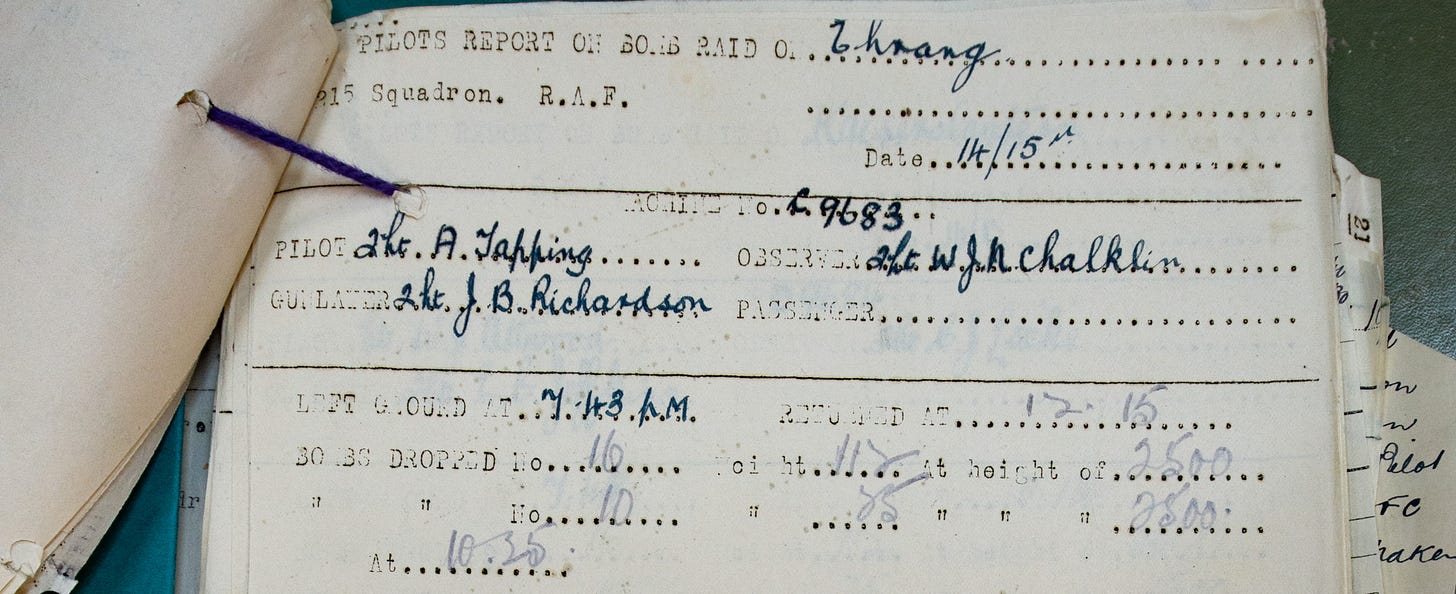

The three men at the centre of this story made up the air crew of a heavy bomber in 215 Squadron, an airplane known as the Handley Page O/400, which I have written about before. The pilot was Alfred Tapping, a 23-year-old from Revelstoke, British Columbia who had signed up with the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force earlier in the war. The observer was Jack1 Chalklin, a 26-year-old from London. And the gunlayer, also a qualified pilot, was John Buckland Richardson (JBR), a 19-year-old originally from Lichfield, near Birmingham. JBR was my great-grandfather.

Tapping and Chalklin had flown combat missions before, but for Richardson this was his first, which probably explains why he was assigned as a gunlayer rather than putting him in charge of his own plane. Richardson had been through 11 months of training and earned his wings, and now was his time to enter the theatre. It would be a night to remember.

Even after more than 100 years has passed, and long after everyone who experienced it has died, the events of that Saturday night can be brought to life in extraordinary detail, sometimes with minute-by-minute accuracy. I now know pretty much exactly what happened to JBR and his crew mates on the evening of September 14, 1918.

And yet. And yet I cannot get into their heads and know what they were thinking as they walked out onto the grassy field of the aerodrome, with light fading in the sky and flares burning on the ground to mark out the runway they would soon use.

Chalklin was the only one of the three to keep a diary. His entry from that day is brief, matter-of-fact and offers no insight into what he was thinking: ”I am detailed for a Raid. A rush to prepare.”

Their heavy bomber carried the identification number C9683. It had been packed with more than 2000 lb of bombs. Seven other airplanes were similarly prepared for other members of the squadron.

I am at a loss to know exactly what the men were thinking, but the picture of the scene in my mind’s eye is more intense than watching a film. It’s like I am physically there. I smell the smoke and the fog in the air. I hear the men chatting as they smoke cigarettes and pipes. I see the excitement on the faces of some, fear on others.

The light fades, the mission begins

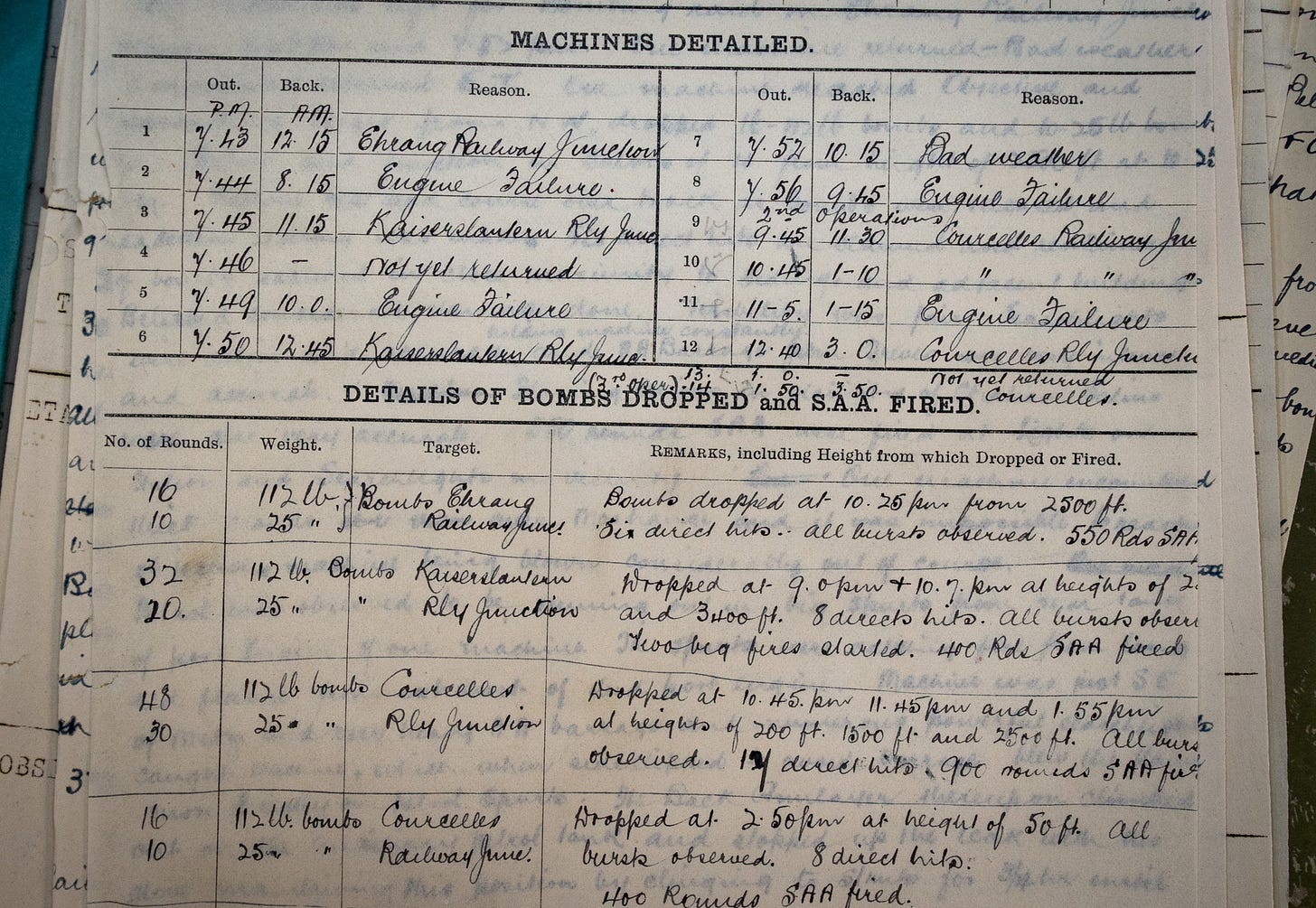

With Tapping as pilot, Chalklin as the observer and JBR behind one of the machine guns, they were the first of the squadron to take off, at 7.43 p.m. Tapping would have lined the airplane up at the end of the runway and given full power to the two Rolls Royce Eagle VIII engines.

Lifting off, the ground receded away from them as they climbed toward the dark grey clouds that were sitting at 6000 ft. A crescent moon was in the sky until nearly midnight, but it probably wasn’t visible through the clouds. By 7.56 p.m., all eight planes of the squadron were in the air and on their way to the targets.

Tapping, Chalklin and JBR had orders to bomb a railway junction at Ehrang, on the outskirts of Trèves (now known as Trier). The exact route Tapping flew isn’t known, but it probably wasn’t direct. Had he flown straight north, it would have been the shortest distance, but it also would have taken them into enemy territory sooner.

Tapping instead took more than two hours to reach the target area, probably because he was trying to stay over friendly territory as long as possible. It’s likely he flew northwest over France for a while, then crossed the front line and turned towards Ehrang. Would they have seen the notorious trenches far below? Probably, because they’d be looking for them. Once over enemy territory, they knew what was waiting for them.

Flying at night in these early years of the airplane would have been scary, but it also had its advantages over daytime flying. The cover of darkness meant it was harder to be seen by those on the ground with the anti-aircraft guns. It was also harder to be spotted by enemy aircraft, and easier to slip away undetected.

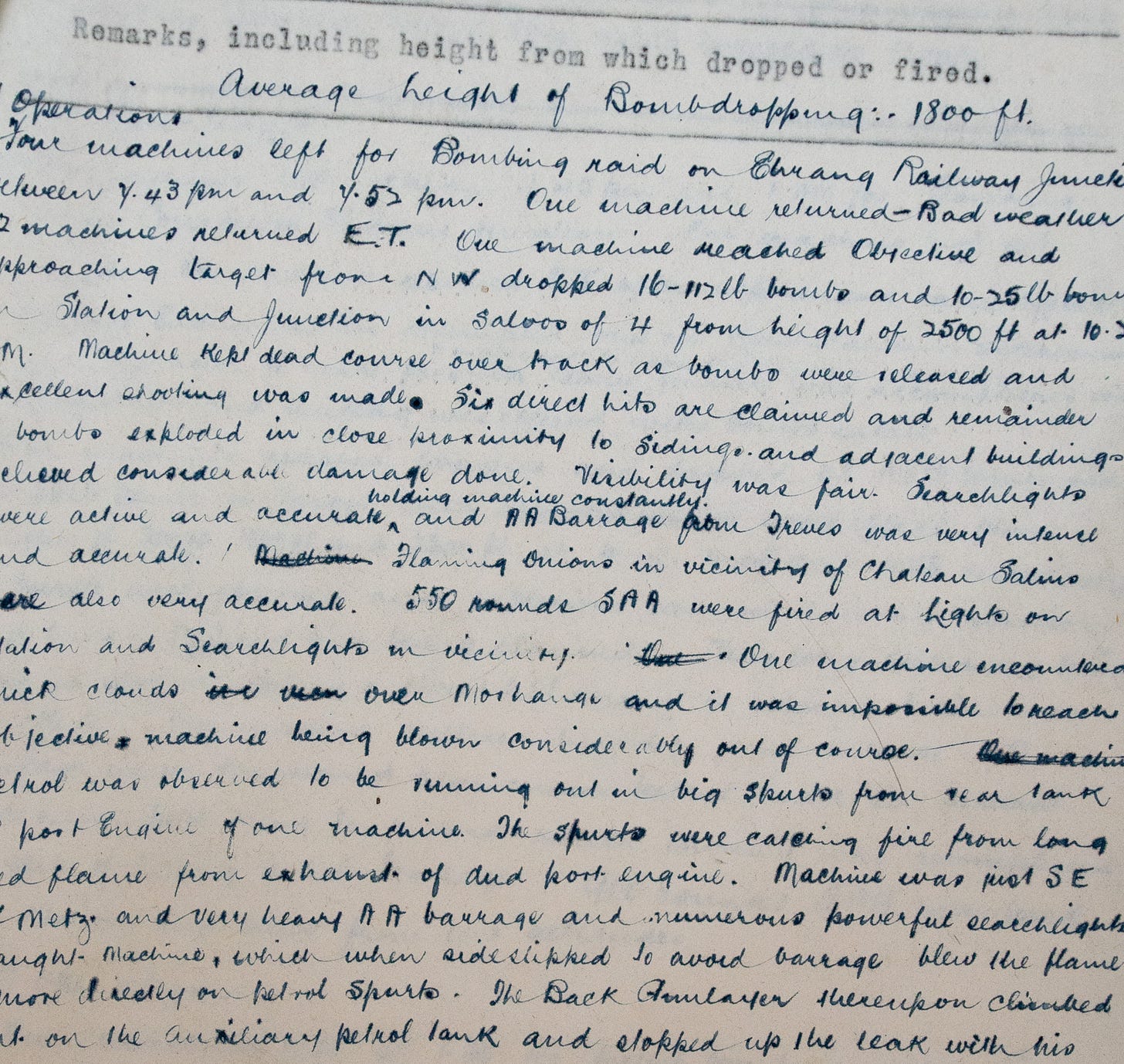

However, the Germans on the ground also had searchlights. At Trèves the lights were described as “active and accurate.” If Tapping and crew were to get caught in a searchlight, anti-aircraft fire would surely follow. Whether they did or not, it didn’t stop them, because they made it to the target area by about 10.25 p.m.

By this time they were 2,500 ft in the air, and despite the cloud cover, the three men could clearly see the railway tracks, station, trains and buildings they were planning to blow up. Tapping flew the bomber straight along the path of the railway in a southeasterly direction, while Chalklin and JBR dropped bombs, some of which weighed 112 lb each. Six made direct hits on the railway junction, destroying buildings and a considerable amount of track.

Throughout all this, JBR was also firing 550 rounds from the machine gun, mainly at searchlights in Ehrang in an attempt to take them out.

A few minutes later they spotted an enemy aircraft near Trèves, probably a Gotha. A German heavy bomber, it was similar to the O/400 both in looks and performance. But it was flying at a higher altitude to them, a clear advantage. It was time to get out of there.

The race for home

Tapping’s route back into friendly territory appears to have taken a straight line south. But just as they were approaching the front line and relative safety over the skies of France, they flew into another threat that could have ended their mission.

At Chateau Salin, the Germans were using an anti-aircraft gun known as a “flaming onion”. It would fire artillery shells into the air in rapid succession, and they would light up. They could reach thousands of feet in the air, and on this night they were described as “very accurate.”

Not accurate enough though, because Tapping, Chalklin and JBR landed back in Xaffévillers at 12.15 a.m. unscathed.

Of the eight aircraft from 215 Squadron that took off that evening, three returned early with engine trouble and one because of bad weather. Another went missing and didn’t return at all.

For those who did return, their night was only half over. Often, night flying squadrons would make their first mission after sundown around 8 p.m. and another one around 1 a.m.

Tapping, Chalklin and JBR were on the ground for about 45 minutes before taking off for their second flight of the night. Just enough time to grab some food, and for the ground crew to reload the plane with bombs and fuel.

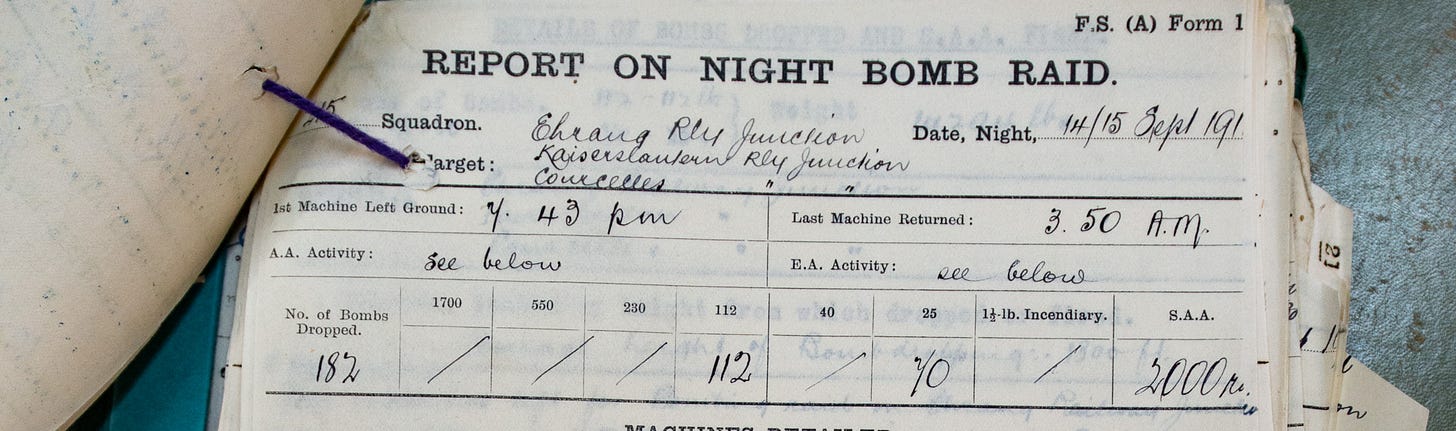

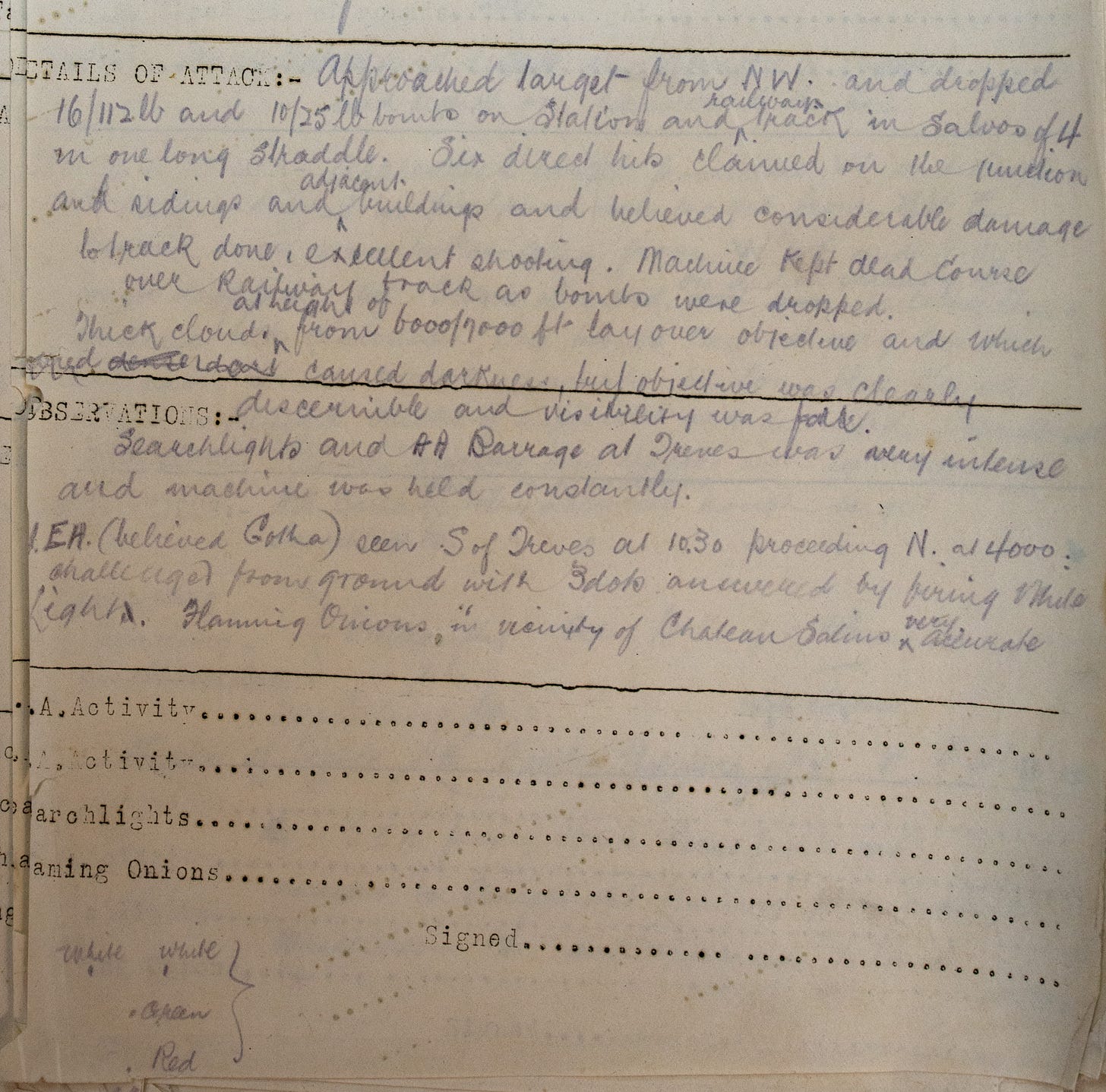

It was also just enough time for someone to debrief the three men on what had just happened. The document pictured above and below was probably filled out in the minutes after the three men landed. They would have been interviewed while their memories were fresh, and when details wouldn’t be confused with what happened on the second mission following it.

It’s almost like looking at the script or storyboard for a film. There’s no way to know exactly what the men said or how they phrased what happened to them or what they were feeling after the mission. But the facts on the page are enough to recreate the events, and imagine how it went.

There is a spot at the bottom of the document for a signature but that line is empty. There probably wasn’t time for the official to scribble their name on the dotted line. They were probably moving quickly, making sure the air crews were debriefed before taking off again, and the filled-out form would have then been passed on to others to use for more comprehensive reports that incorporated the information from other aircrews.

Just before 1 a.m., Tapping, Chalklin and JBR were back in their bomber aircraft, and as the clock struck the hour they taxied to the runway and took off. This time they were headed for a railway junction at Courcelles, just east of Metz.

This time, however, it ended differently. By the time the sun came up, they had not returned to the aerodrome. Reports listed them as missing from the bomb raid, and no one knew what had happened to them.

Now, of course, we do know what happened. That will be part two of The night that changed three RAF airmen forever.

The original version of this story referred to John Chalkin, not Jack. Official documents list his name as John but his family tell me he was always known as Jack.

Ack! Thank you Eleanor. I don't know how I made that error but the spelling of Jack Chalklin has now been corrected.

Fascinating - thankyou David! Also, just to say that Jack's surname was Chalklin - with an 'l'!