What’s the scariest thing about being captured by the enemy in a war? Execution? Torture or other forms of mistreatment?

The First World War felt never-ending for most of it, and featured a level of brutality not previously seen. Millions were killed. Upon capture, it would be reasonable to fear that you’d simply be executed.

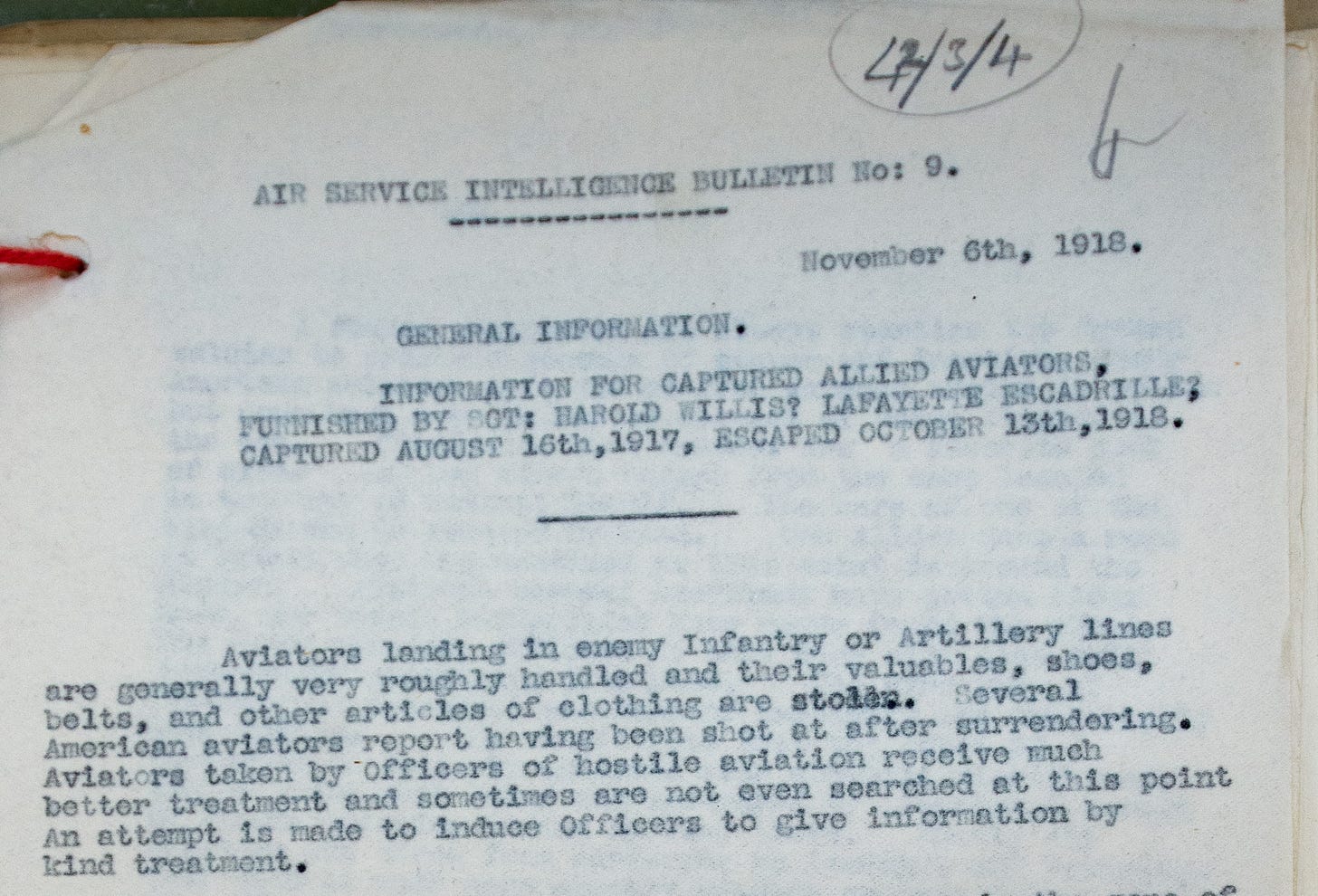

In an intelligence bulletin written by Sgt Harold Willis in November, 1918, (who had been held captive for more than a year before escaping) he offered good reason to fear the worst. “Several American aviators report having been shot at after surrendering.”

However, the more likely treatment for most was to be “very roughly handled and their valuables, shoes, belts, and other articles of clothing are stolen.”

Take the word of Daniel Owens, a pilot with 55 Squadron who got into an air-to-air fight with a bunch of German aircraft in 1917.

He and his observer, Harker, were both wounded in the air. Harker was shot in the leg, shattering the bone above the knee. Owens says he was hit in the left eye, “with the temple bone broken.”

Harker fell unconscious as Owens struggled to shoot back and keep control of the airplane, which was increasingly impossible.

They crashed, and when they came to a halt both men were somehow still alive. Three enemy planes landed nearby and the pilots moved in on foot. Owens tried to shoot them with his Vickers gun, but failed. Then one of the German pilots hit him over the head and knocked him out.

When he woke up he was still lying in a field. From here, Owens recounts the story in his sardonic tone.

I was in the hands of two of the most accomplished thieves that it has ever been my privilege to come in contact with... All my flying kit, my trench coat which I wore underneath my flying coat, ankle boots which I carried with me in the buss [airplane], my purse and over 170 francs, identity disc, silver flask, and other trifles too numerous to mention were all scooped by these gallant officers.

From here, the two men were put into a farm wagon and taken to a house, where German soldiers gawked at them until a doctor arrived. Owens describes some pretty shabby medical treatment, and then, a small bit of retribution. “I was sick, oh so beautifully sick all over the aforesaid doctor’s spick and span tunic, iron cross and all.”

Once at the hospital, Owens says an interpreter stole his watch. “Taking it all together, I have come to the conclusion that they did rather well by me.”

Be prepared!

No doubt all aviators knew that being captured and imprisoned was possible, even likely. For that reason, they were given plenty of advice on what to do if it happened.

Members of the RAF’s Independent Force were at high risk of capture. They flew over German territory day and night for months on end, dropping bombs and trying to dodge anti-aircraft fire. Many were forced to land in enemy territory.

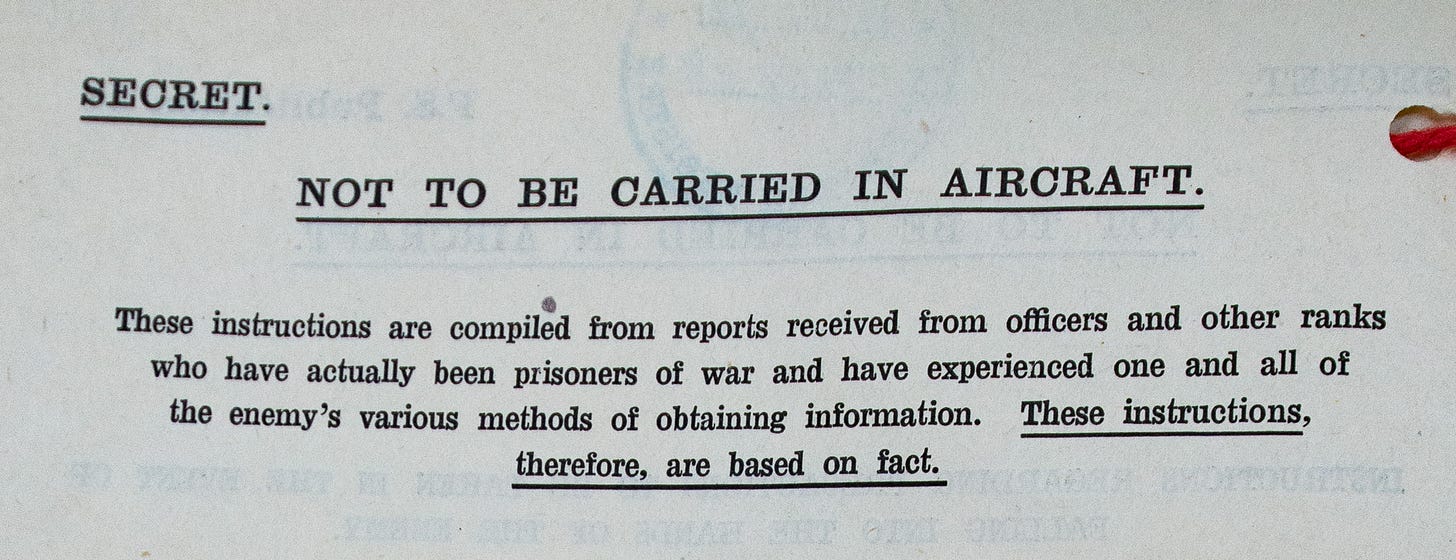

In July, 1918, these airmen were issued a secret document from headquarters titled, INSTRUCTIONS REGARDING PRECAUTIONS TO BE TAKEN IN THE EVENT OF FALLING INTO THE HANDS OF THE ENEMY. It lists 28 instructions, all of which were to be memorized, since carrying the document with them on the aircraft was forbidden, for obvious reasons. I found a copy of it in the National Archives, London.

It addresses the issue of execution head on, in boldface type. “The enemy dare not carry their threats into execution, and a prisoner who systematically refuses to give information is respected by his captors.”

This point seems debatable.

More than anything, aviators were told they should assume they’d be captured. This meant taking no papers with them in the airplane, not even maps if it could be avoided. Nothing personal either, not even pictures of loved ones. As I mentioned in last week’s story, every man was told to turn his pockets inside out as he approached the aircraft, a ritual to ensure nothing was taken on a flight that should have stayed behind.

Shut up!

If there’s a single theme to the 28 instructions, it is: keep your mouth shut. The enemy will use threats and intimidation, but also various tricks and inducements to get captured men to talk. All must be resisted.

Instruction no. 3 says, “don’t assume anyone is a friend because he wears British or Allied uniform and appears to be a prisoner like yourself, or because he speaks perfect English. He may be an enemy agent.”

In his intelligence briefing, Sgt Willis describes one guy everyone should watch out for if they end up at the prison in Montmedy. He was a Frenchman, about 22 years old, 5’10” with broken English. His eyes were blue and “too close together,” had an unclean appearance, pimply complexion and “retrousse nose.” He lived in a special room by himself, meaning he was a member of German Intelligence whose role was to pry information out of captured officers.

In addition to these planted agents, other tactics and tricks were used to get men to talk.

don’t assume that a nurse or attendant is a friend because she professes to be a neutral and secretly to sympathise with the Allies. She may be an enemy agent

don’t allow wine to unloose your tongue

don’t be deceived by a friendly reception on capture or by good treatment, which may only be temporary and of set purpose.

These walls have ears

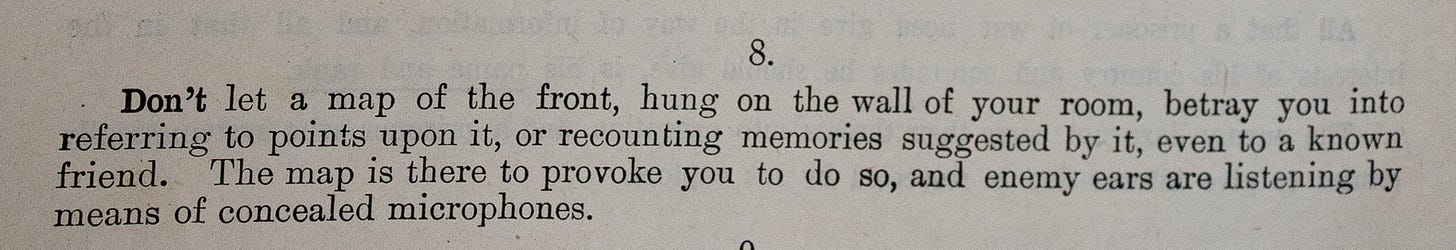

One of the most interesting tricks was the use of microphones. Germans would bug rooms so they could always be listening. Then they would do things to try to spark conversation.

A holding cell would have a map of the front on the wall. With no one else in the room, two prisoners might start recounting memories of where they had been and what they had done. But the microphones would be listening.

Prisoners might also get thrown into solitary confinement for a few days, then released into a room with a friend. Desperate for conversation, they’d start talking. But the microphones would be listening.

The prison camp at Karlsruhe was infested with them. Sgt Escadrille says it was “lavishly equipped with electric microphones, two of which were found and destroyed by Lieutenant Savage of French aviation during my stay there.”

Even in rooms without microphones, expert interrogators would try to engage prisoners in conversation, even on seemingly unimportant subjects.

Again, shut up! The only thing officers were required to reveal was their name and rank. “The enemy knows this is the full extent of the obligation upon you...and will respect you more if he sees that in captivity equally as in action you discharge your duty to your country.”

In other words, you will not be executed or punished for keeping your mouth shut.

Of course, there was no guarantee of this. The Hague Convention of 1899 forbid the execution or mistreatment of prisoners. It also outlawed the use of chemical weapons, but the various powers in the war used them anyway.

The only real hope in the instructions comes at the end. Although, “don’t be downhearted” isn’t all that helpful, it does also say opportunities for escape will present themselves.

So how do you escape when captured? I’ll get into that next week.