The night that changed three RAF airmen forever (part two)

When you're forced to land inside enemy territory, life starts to get extreme

This story picks up where part one left off. If you haven’t read that, it will still make sense if you want to start here. But if you want to begin at the beginning, I suggest you go back to part one.

Our scene opens at the Xaffévillers aerodrome in France shortly after midnight. Flares of burning paraffin would have marked out the landing strip. The orange glow from them pierced through the thin fog, calling out to any pilot in the night sky who was looking for them.

Alfred Tapping, Jack Chalklin and John Buckland Richardson (JBR) must have been glad to see that line of glowing lights as they descended from a 4.5 hour flight in their heavy bomber. Their night was already one to remember, having blown up parts of a railway junction in Germany, dodging untold amounts of anti-aircraft fire, and returning without a scratch.

I haven’t been able to find any photos of what I’m describing. It’s doubtful any exist, since it would have been technically difficult, if not impossible, to capture fast-moving action at night with the cameras of the time.

Fortunately, the observer on the flight, Jack Chalklin, not only kept a diary, but also drew a few sketches. Check this out:

I have to thank Chalklin’s grandchildren for sending me a copy of the picture, as well as a copy of his diary and other information he told them years ago when he was still alive. It helps fill in what happened that night with details that are not available from any other source.

But the night was only half over. In 45 minutes they’d be back in the air for the second bombing run.

By this time the clouds were thicker. Reports from others at the time said the weather had turned worse as night set in. The moon had been hidden behind the clouds earlier in the evening but was now long gone from the sky.

If the three men were following their training, all their pockets would have been turned inside out as they approached the aircraft for the next flight.

The ritual — required of all airmen — served as a reminder not to carry maps or other papers of any kind, not even photographs of loved ones. If they were to be forced down and captured by the enemy, any of these documents could be used against them, and would deliver valuable intelligence into the hands of the Germans.

They took off at 1 a.m., this time headed for the railway junction at Courcelles. It would end in an entirely different way from their first flight of the night.

How the hell did we survive that?

Of course, they didn’t know that yet. An air of confidence must have permeated the cockpit as they climbed towards the clouds. The first flight had gone well. They had successfully carried out their orders, unleashing hell on a German train station.

Just the fact that their airplane kept working long enough to get them to the target and back must have felt like a victory. Two other planes in their squadron had to return early to the aerodrome with engine trouble, still fully loaded with bombs.

Although they may not have been deep in reflective thought at the time, it’s kind of amazing to think of what Tapping, Chalklin and JBR had just gone through (along with so many other pilots and airmen flying similar missions).

Since the sun set a few hours earlier, they had seen and experienced things that most men on earth never would. Less than 15 years after humans had figured out powered flight, these guys were speeding through the clouds at 90 mph in one of the largest airplanes in the world. It would have been cold, loud and relentless up there, but would it not have been exciting too?

They were in a flimsy machine that was barely airworthy, with engines that could stop working at virtually any moment, bullets flying all around them. If I had come back from that unscathed as they did, I would have been thinking, we just got away with that?

An apocalyptic scene

Courcelles is about 80 kilometres to the north of the Xaffévillers aerodrome, but the route they took is hard to guess. It seems likely they followed a fairly direct line, arriving in the vicinity of the target area sometime after 2 a.m.

In recounting the moment years later to his family, Chalklin said that for the bombing run they cut power to the engines, glided down to 50 ft. and began dropping bombs.

It seems at least one bomb got jammed somehow. Tapping told Chalklin to push it out with a broom handle. He did, but it exploded just after it was released, and blew the plane upwards. While all this was happening, they were also trying to dodge relentless anti-aircraft fire.

Within minutes, luck ran out.

Chalklin says a petrol pipe was shot through. Fuel began spraying all over the place, and covered JBR in it. Unable to restart the engines, there was no way they’d be able to stay airborne.

Tapping had no choice but to land the plane well inside enemy territory.

They descended into what must have been an apocalyptic scene. By this time it was 2.30 a.m. Just a few kilometres from where they were forced to land, three other planes from 215 Squadron had hit the Courcelles railway junction with dozens of bombs, reporting 17 direct hits. Trains and track were destroyed, as well as the station.

A huge fire was reported to be burning in Metz. And twenty minutes later, another heavy bomber from 215 Squadron swooped in to hit the railway junction again. It dropped all of its bombs at 2.50 a.m. This is from the official report of the raid:

Visibility in this instance had become poor so machine descended to 50 ft. to distinguish target and effectively bomb it. Two runs were taken, from E. to W. and from W. to E. lights from Station being extinguished on approach of the machine. All bursts were observed and 8 direct hits with 112 lb. bombs on Station and Junction claimed. It is thought that considerable damage was done. Railway station was then raked with machine gun fire, 400 rounds being fired.

The report concludes that Metz and numerous other towns, “were all well lit up.” The whole region would have been a scene of fire, destruction, and of course, death.

You have your orders

For Tapping, Chalklin and JBR, there’s no record of what the landing was like exactly, but they touched down somewhere north of Metz. It seems all were unharmed, except that JBR was covered in petrol.

What did they do next? There’s no specific record of that either, but their orders in this scenario were clear: set your airplane on fire.

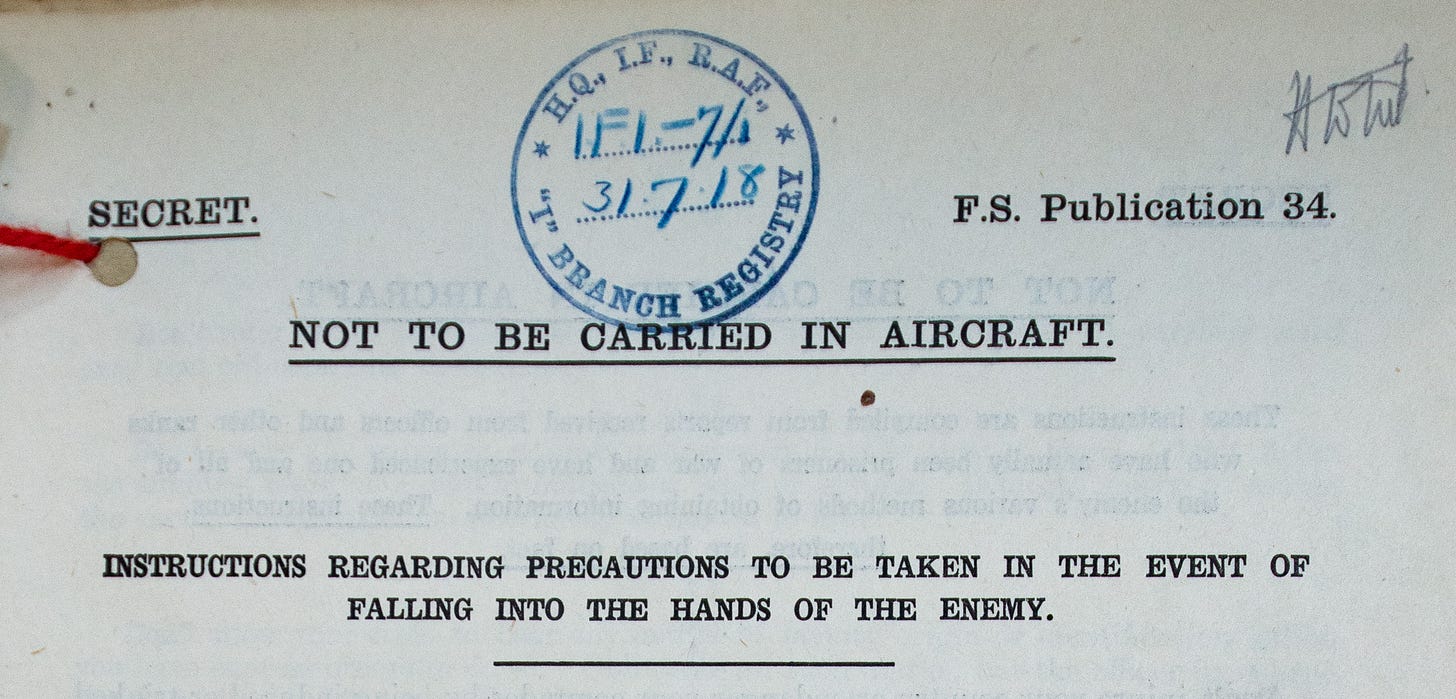

“Don’t forget to destroy, if possible, your machine, maps, &c., by fire if brought down.” The order was contained in a secret document given to all airmen, titled “INSTRUCTIONS REGARDING PRECAUTIONS TO BE TAKEN IN THE EVENT OF FALLING INTO THE HANDS OF THE ENEMY,” issued on 31 July, 1918 from the headquarters of the RAF’s Independent Force1. It also carried the directive that pilots and airmen must not take the document with them onboard the aircraft, for obvious reasons.

The secret four-page document lays out the stakes. It says the enemy will try to gain any advantage it can from a downed airplane and documents inside it. Letting an intact airplane fall into the hands of the enemy was not acceptable.2

So, if Tapping, Chalklin and JBR did as they were trained, they would have set fire to the aircraft before abandoning it.

Then they headed into the woods.

When a German greets you on the road, what do you do?

They found the Moselle, a river that runs through Metz, and followed it south. Throughout the dark early morning, the sunrise hours and into the next day, they hid amongst the trees. They had no food. Beyond hiding from the enemy, it’s not clear where they were trying to get to except that the front line would have been to the south.

By Chalklin’s account, it was miserable. Trekking through dense forest would have been slow and difficult, and there was little hope of finding any food there. They decided to take their chances and walk along a road instead. A German guard passed them and greeted them with a “guten morgen.” He grew suspicious when they failed to respond, and arrested them.

Chalklin says the guards were friendly and gave them food and drink after they took them to Fort Monteuffle in Metz. They slept in the guardroom overnight.

The next day, Monday 16 September, 1918, the three men were put on a train to St Avold where they were “interviewed and locked up,” as Chalklin succinctly puts it in his diary.

And so Tapping, Chalklin and JBR began their time as prisoners of war.

What future for a captured airman?

I try to put myself in their position. They would not have known where they’d be held, where they’d be taken to. They had no idea what conditions they’d face, how long it would last. Would they be treated well? Thrown into solitary confinement? Put on trial? Executed? Left to starve to death?

It’s easy for us, living a century later, to take comfort in the fact that the war would be over in less than two months.

But of course, they didn’t know that at the time. There were predictions that the war would last for years, even that it would have no definitive end. The idea that Europe would persist in a permanent state of war was far from unthinkable. What would happen to POWs in that scenario? How could they avoid falling into despair? How could they even dream of surviving and making it home?

The Independent Force was a unit of the RAF based in and around Nancy, France. Its role was to strategically bomb Germany day and night in an attempt to weaken the enemy and help win the war. It was “independent” because it set its own objectives, rather than taking orders from the army or navy. Tapping, Chalklin and JBR were part of the Independent Force. I will have more to say about it in future, but I’ll leave it there for now. There’s a lot to explore. Entire books have been written just about the Independent Force.

This remarkable secret document is full of instructions that deserve more attention. I’ll be writing about it in detail next week.