My great-grandfather, JBR, enlisted with the British military a few months after turning 18 years old, in 1917. He joined up with the Royal Flying Corps (a predecessor to the RAF) and immediately began 11 months of intensive flight training. He didn’t know how to fly before that.

Ever since I first discovered this, I wanted to know how this came about. Had he been interested in learning to fly from an earlier age? Did he do anything to prepare for that before he turned 18? Was he interested in flying specifically or just trying to avoid the infantry? By the time he was of age, the horrors of the trenches would have been well-known.

What was flight training like? In the early days of the war, pilots were given a few months of instruction at most, and then thrown into the theatre. But by 1917, after so many deaths by what can only be described as pilot error, the air forces had expanded the education of pilots significantly. JBR benefitted from this, but what were the details?

Also, as the war dragged on, demand for pilots grew rapidly. Not only had many been killed in combat and accidents, but the air forces were expanding as fast as they could. In 1914, it wasn’t even clear yet what role airplanes would play in warfare, or how useful they would turn out to be. Britain had a few hundred pilots at the outset, none of whom had extensive flying experience because humans had only been flying airplanes for barely a decade. By 1917, there were tens of thousands of pilots with the RAF, and an insatiable demand for more. Generals needed something to break the stalemate in the trenches and give them the edge to win the war. Air power might be the answer, they thought.

Was JBR responding to this? Thinking he could be part of the effort that would hand Britain victory? Maybe. But JBR’s path into the air force was not a snap decision he made on his 18th birthday. It had been planned since his early teens.

Schoolboy

JBR came from a family of Quakers on his mother’s side. Her family name was Burtt, and their history in Lincolnshire is well-documented for hundreds of years back. Quakers, among many other things, are known for refusing to participate in war.

JBR’s father, James Richardson, however, was not a Quaker, and would have had far more say in the boy’s future than his mother.

It’s not known if there were any disputes in the family about JBR wanting to pursue a military career. By the time he was a teenager, the First World War was on and any man turning 18 at that time would have been expected to sign up. Many Quakers were conscientious objectors and would have been unwilling to fight, although some were willing to participate in non-combat roles such as medical services.

Whatever the case with the Richardson family, Quaker pacifism appears to have had little influence on JBR’s life.

As a boy, he had attended Queen Mary’s Grammar School in Walsall, just outside his home of Lichfield (north of Birmingham). The school was founded in 1554 by Mary Tudor, and to this day educates students from the ages of 11 to 18. JBR entered the school in 1912, when he was 11 years old. He could have stayed there for the rest of his education, which would have made sense as it was close to home. But that didn’t happen.

In 1915, he moved schools. He became a boarder at the Wellingborough School near Northampton, which was more than a hundred kilometres away from home. Nearly as old as his previous school, it was founded in 1595. Why did he go there? Queen Mary was a state school and would have cost nothing to attend. Wellingborough doesn’t have records about what the fees were in 1915, but for a boarder they wouldn’t have been nothing. Why would his family have been willing to pay for him to do this?

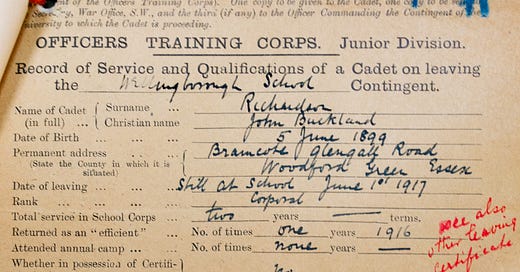

It appears the answer is that 14-year-old JBR, with war now raging in Europe, had decided his future was in the military, and his family was prepared to help make that happen. Wellingborough School had an Officer Training Corps (OTC), which was a cadet program for teenage boys. Wellingborough had established it in 1900 (then called a Cadet Corps), attached to a volunteer battalion of the Northamptonshire regiment. The program expanded and changed its name to OTC in 1908. At the time nearly a hundred schools in Britain had such programs.

The OTC was a virtually guaranteed path to becoming a junior officer with the British military at the age of 18, but Queen Mary didn’t have one. This is almost certainly the reason, and maybe the only reason, why JBR switched to Wellingborough.

The OTC there featured a lot of shooting practice, as well as combat drills. On the playing field, timber frames were erected and bags of straw were hung from them, to represent enemy soldiers. Students would charge at them with bayonets in simulated battle.

One thing JBR did not learn at Wellingborough was how to fly. The school was one of the first in the country to start an Air Section, but that wasn’t until 1937. So despite the education and training he received there, flight school would not come until after enlisting.

I haven’t been able to find any surviving records of JBR’s academic performance, but reports of what kind of soldier he would make are available, and they are favourable. As he was finishing his time at Wellingborough in the spring on 1917, JBR’s Record of Service and Qualifications of a Cadet upon leaving showed that he was a 1st class shot, his general efficiency was “good,” and he had learned some morse code and semaphore. He was athletic but with only fair abilities in that department, and it noted he was a “good disciplinarian”.

Finally, the Royal Army Medical Corps gave him an examination, declared him fit for service, and noted his excellent eyesight (6/6, or what is commonly called 20/20 vision).

Enlistment

JBR turned 18 years old in June but what he did over the summer is a mystery. He enlisted with the Royal Flying Corps on 5 September 1917, and it appears he learned to do virtually everything related to aviation before seeing combat.

Less than two weeks after signing up, on 17 Sept, JBR was sent to Halton Park, an RFC training facility just south of the Lake District. The land was owned by Alfred de Rothschild and had been used for military purposes since 1913. At the outbreak of war, he offered it up to the military for full-time use. In 1917 it became the RFC’s main facility for training aircraft mechanics. Permanent buildings were constructed and all aspects of aircraft maintenance were taught. When JBR arrived, it would have been a big, busy place, with thousands of people being trained at any given time. They learned everything from how to fix and rebuild engines, maintain airframes, build and take care of instruments, and more.

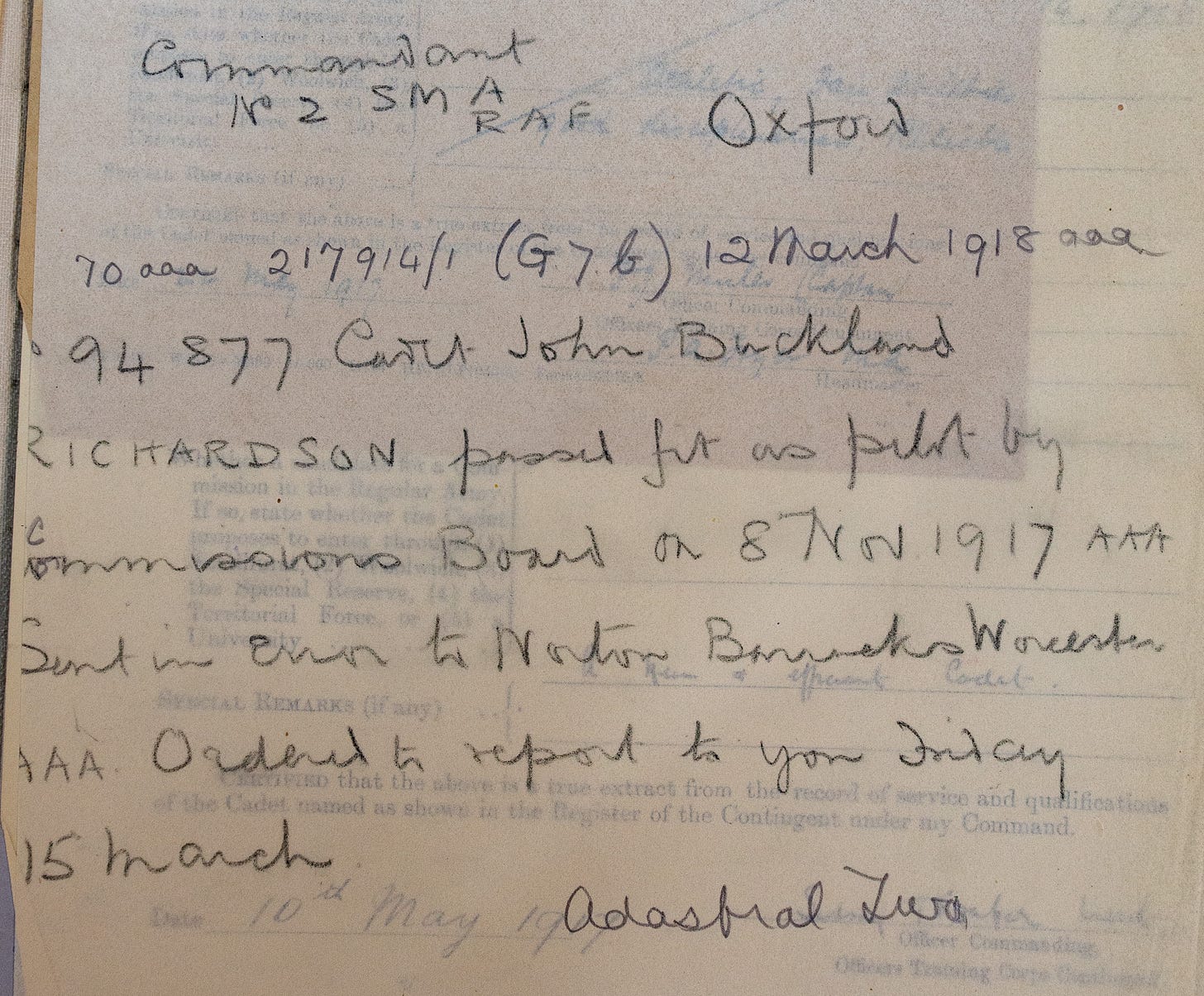

JBR spent a few months there, probably learning how to be an aircraft mechanic. On 8 November 1917 he was declared fit as a pilot by the Commissions board. But did this mean he was ready to fly? Unlikely. The declaration was probably that he was fit to start training as a pilot, not that he had already done it. The air forces had learned their lesson from earlier in the war when pilot training was quick and rudimentary. More pilots died in accidents early in the war than in combat.

But here a mistake seems to have been made. From Halton Park, JBR wasn’t sent to pilot school initially. He was sent to Norton Barracks in Worcester to train as an observer. These non-pilot air crew were navigators and aerial photographers. They were experts in map reading and in taking pictures from the air. Observers were crucial members of the air forces, without whom the pilots wouldn’t know where they were going, and without the aerial photographs, detailed maps could not have been made. But observers were not taught how to actually fly the planes. JBR spent months at this facility until March of 1918, when a memo notes that he had been sent there in error.

On 15 March, he was sent to the School of Military Aeronautics (S.M.A.) in Oxford, “for instruction in aviation.” It appears that an administrative mistake was made the previous November, when someone sent him for observer training instead of pilot training. Whatever happened, JBR had spent about four months learning something he would never put into practice.

At S.M.A. though, he did learn to fly. The air forces had two of these schools at the time, and they taught recruits everything there was to know about the science of flight, which wasn’t much compared to today. They learned how the particular aircraft of the RFC worked and how to operate them. And of course, they went on flights with instructors. I have written before about what flight training consisted of at that time and what JBR experienced in detail, and you can read it here.

In August, 1918, JBR became a qualified pilot with a commission of 2nd Lieutenant. He was attached to 215 Squadron, part of the Independent Force, based in and around Nancy, France. On his first night of active combat, he and his crew mates were forced down in enemy territory and captured as prisoners of war by the Germans.

Lingering questions

After piecing together this prequel of JBR’s life in the First World War, there are still questions. I was hoping to find evidence, or at least clues, that would explain why JBR wanted to learn to fly. When he was a teenager, airplanes had existed for barely a decade, and it’s unlikely he would have known anyone who’d been in one. What was the attraction? Or, as I suggested at the beginning of this story, was flying more about avoiding the trenches?

Learning to fly would have required a willingness and ability to commit to academic study involving math and physics, something not every young man could do, or wanted to do. JBR was obviously willing, but again, what was the motivation? An interest and curiosity about aviation and physics? Or was it a belief (largely justified) that serving in the air forces would be less horrible than the infantry (if not any less dangerous)?

And if he was genuinely interested in aviation, why did he abandon it after the war and never fly again? Traumatized by experience? Or never had a passionate interest in the first place?

These are all questions I will unlikely ever be able to answer. It comes down to a question we ask of ourselves and each other all the time: why do we do the things we do? There’s no way to know unless we talk about it or write it down. Without that, the reasons for our actions evaporate into nothingness, and become an unsolvable mystery for those who come after us.