Flying and spying

Spying is as old as wars themselves. But with the first World War came a new way to deliver them into the action

Secretive and mysterious, spying is a world of deception. It’s full of betrayal and treason, where nothing is as it seems and where trust is transactional and elusive. It’s about getting information you’re not supposed to get, so it can be used against the people it came from. The stakes couldn’t be higher — it’s often about winning a war, or defending your country from defeat or annihilation.

No wonder the world of fiction includes a rich genre of these stories. The characters, plots, double lives, lies, the glamour of floating through society as someone you’re not. Reading these stories can be aspirational (I wish I led that life!) and at the same time, cautionary (thankfully, I don’t live that life).

We all know about James Bond and Jason Bourne. We know about the John le Carré and Tom Clancy novels. Long before them there was Rudyard Kipling, Joseph Conrad, and the list goes on and on. Of course, many of those stories are based at least partly on real events. Ian Flemming famously worked for Britain’s intelligence services, as well as being a journalist.

In the realm of non-fiction, I remember in university there was a course on the history of espionage. I didn’t take it because it was full by the time I’d heard about it. Students from all sorts of disciplines enrolled, not just history majors. The appeal is obvious.

Infiltrating the enemy and stealing secrets have been around as long as wars have. But when the First World War came along, spying had a new, powerful tool at its disposal. One that allowed spies to drop into the action in a way that was previously unavailable. Flying.

Everything is better with music

The Royal Flying Corps started taking spies behind enemy lines in 1915. It didn’t go well initially. In what was apparently the first attempt, the pilot hit a tree on landing in a small field. He and his spy were seriously injured, then captured and held as prisoners. Meanwhile, civilians made off with pretty much everything in the airplane.

Other stories illustrate the sort of characters who volunteered to act as secret agents. In 1917, at an airfield in northern France, a British pilot was preparing to fly a French spy over the lines. As he waited on the airfield, bombs from a German attack fell nearby. He was impatient to get going, but the spy clearly had his own ideas about how this occasion would go down. The Frenchman, described as “gallant,” brought a gramophone onto the airfield with a record of the Marseillaise on it.

It’s like the opening to a movie. Bombs are exploding all around, pilots are pacing around impatiently, wondering how much time they have before the airfield itself gets attacked. Meanwhile, our French spy, dressed in peasant clothing as a disguise, will not be rushed. He is playing the music at full volume and singing along as he climbs into the airplane.

Except that the spy couldn’t just settle into the second seat of the plane. He was wearing a parachute, the idea being that he would jump out and float down into enemy territory. But parachutes were bulky at that time, and cockpits didn’t have the space to accommodate them. So the spy had to be strapped to the top of the fuselage. Maybe the Marseillaise was the distraction he needed from the insanity of what he was about to attempt.

The plane took off, the spy still singing, but there’s no word on what happened to him.

Maybe this isn’t a good idea after all

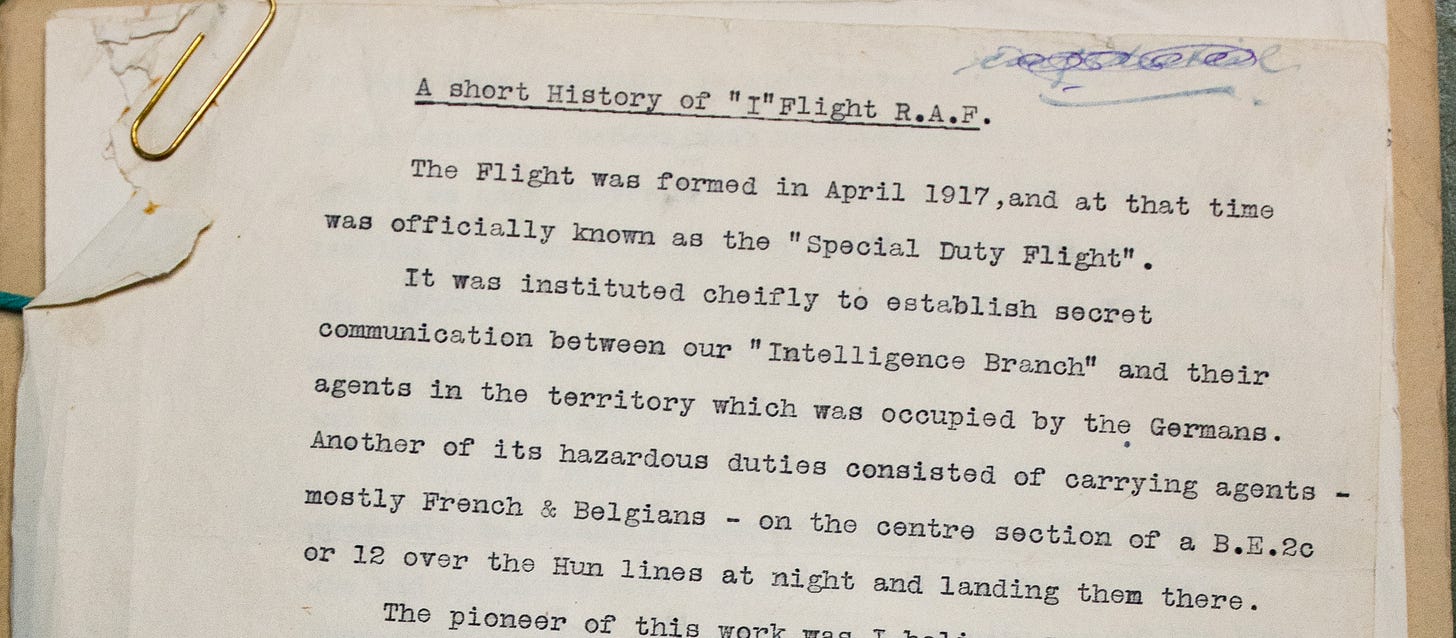

A report on these spy operations is cryptically titled, ‘A Short History of “I” Flight R.A.F.’ (presumably the “I” stands for intelligence).

It notes another incident in which a spy has second thoughts after he and his pilot were already in the air and headed to the drop point. The spy decides he’d rather stay on board than jump out with his parachute, while the pilot insists that he do it anyway. The two start fighting in mid-air. The spy tries to grab the stick and the pilot almost loses control of the plane. Eventually the spy jumps out, never to be heard from again.

The psychological terror of this is understandable. Flying, as I have mentioned before, was still new and most humans had never done it. Few men had experience with parachutes either. They weren’t issued to British aviators, and for the most part they were only used for special operations such as these spy drops. So when a spy was told to jump out of an airplane in mid-air, there’s a good chance he was operating with zero experience.

The “I” Flight report acknowledges this:

The latter story can be well understood, as being dropped from a machine at night, never having been in a parachute or an aeroplane before, must necessarily have a somewhat terrifying effect on ones nerves, not overlooking the fact that, after landing in enemy territory the unfortunate man has to confiscate the parachute … and all its harnesses, before he can make friends and commence to gather information.

The mental stress placed on aviators was frequently mentioned at the time, but was also poorly understood. As the quote above shows, often it’s characterized as an unfortunate consequence that isn’t necessarily avoidable. The mental effects of flying at that time is a fascinating subject that I’ll explore in a future instalment.

You’re a pilot? Well now you’re a spy

Then a remarkable story emerges from summer, 1916, of a British 2nd Lieutenant and a French agent. No parachutes in this case. Instead the pilot, C.A. Ridley, was to land near Cambrai, drop his man and then take off again. He did land, but engine trouble meant he couldn’t get the plane restarted. He was stranded. So Ridley became a spy too.

He and his French agent wandered around for two weeks trying to pick up what military information they could. Ridley needed to be creative, and he needed a disguise. He didn’t speak French or German. So he painted his cheeks with iodine, bandaged his head and pretended to be deaf and mentally ill.

This seemed to work for a while. But after the two crossed into Belgium, it looked like Ridley’s luck had run out. He was found out and arrested while on a tram. But guys like this tend to make their own luck. He punched the military policeman who was holding him and jumped out of the tram while it was moving.

Having lost touch with his French agent, he was now on his own. He somehow made it clear across Belgium to the border with Holland, where he used a ladder to climb over the electric fence. There he reconnected with British forces and within a week was back at the Somme.

In two months of wandering around, Ridley had learned the locations of ammunition depots, aerodromes and billets, which he told his superiors about. It was a beautiful piece of spy craft.

But as useful as Ridley’s efforts were, it still took a long time to get the information back to those who could make use of it. This sort of intelligence becomes all the more valuable when it can be communicated quickly. Thanks to aircraft, it was now easy to get spies in fast. But how to get their information out just as fast? Enter the birds.

A different kind of ‘wing’

In one of the earliest successful attempts to drop a spy behind enemy lines, pigeons were taken along. In October, 1915, a spy leaps out of a plane that has just landed, carrying two baskets full of carrier pigeons, and disappears into the trees.

He had been dropped there by Lieutenant J.W. Woodhouse, who, after some difficulty, took off again and eventually made it back to British territory. Fittingly, there’s no word on what happened to his spy or the pigeons. But we know how this sort of operation was supposed to go down.

The idea would have been for the spy to collect intelligence about troop movements, enemy positions and so on. Then he’d write what he’d learned on small pieces of paper and roll them into tiny metal tubes on the legs of the pigeons. When released, the pigeons would fly back to where they had come from, delivering the crucial intelligence.

The results were mixed. The “I” Flight report notes a few cases where birds were dropped in with spies that led to successful intelligence gathering.

Where it worked, birds would usually bring intel back within a day, sometimes 10 hours. For a time when instant communications didn’t really exist yet, that was pretty fast. This being spy craft, the report is vague on exactly what information was collected.

But there are plenty of failures as well. Sometimes the operation was such a long shot, it felt like it was being done out of desperation.

On August 17, 1918, the British badly needed information on what movements German troops were making behind the lines between Lille and Douai. But they had nothing, and no spies were known to be in the area.

Twenty-four pigeons were loaded into boxes with parachutes attached. They were put on a plane, which flew over the area and dropped the bird boxes over villages along the railway line between the two towns.

Along with the birds, the boxes contained written instructions for French or Belgian civilians who discovered them. It asked them to write any information they could and attach it to the birds, who would fly back.

The British only realized later that the area was being evacuated at the time. So there was no one around to even find the birds. Not surprisingly, not a single pigeon returned. The regret is palpable in the report. “This was a very unfortunate blow, for the majority of the birds were very highly prized.”

These birds are heroes!

In the report and elsewhere, pigeons are characterized like the spies they serve. They are described as loyal, heroic, committed to duty, and determined to complete the mission, even under duress.

One story goes that a pigeon somehow managed to fly back home with a crucial message, even though it was suffering from grave wounds. It had been shot in the breast and had a leg blown off, but only died after completing the task.

Another pigeon carried a crucial message that would eventually save the lives of four men. It flew into a gale and had to fight high winds, but eventually made it. The bird died of exhaustion upon arrival.