Death from above

People have always known what to do when their city is attacked from the air. Get underground

In the spring of 2022 I began reading stories about Ukrainians spending every night sleeping (and not sleeping) on the trains and platforms of Kyiv’s subway system. After Russia invaded the country in late February, people quickly realized that the subterranean world, normally the domain of commuters, was the safest place to hide from air strikes that happened every day and night, pretty much always with lethal consequences. Missiles and shells, however, could not reach the depths of the subway.

On many nights over the past year in Kyiv, there have been thousands of people down there. Lights in the stations dim around 10 p.m., when people roll out sleeping bags onto the cold floor and try to get some sleep. This routine has continued in varying degrees throughout the war.

Death from above is part of most wars now. Air power and air supremacy are requirements for victory in this sort of conflict. And for as long as air raids have been around, people have been hiding out underground to try to escape them.

We’ve seen this movie before

What Londoners experienced in the First World War is eerily similar to what Ukrainians have faced over the past year. It’s far more lethal and destructive nowadays of course, but it’s possible to look at Ukraine today and draw a direct line back to the 13th of June, 1917, and the events of the following few months.

That was the day London was first attacked by a coordinated group of German airplanes1. There was a light fog in the air but the weather was otherwise clear. Shortly after 11 a.m. people could hear the roar of German heavy bombers approaching the city. But the idea that enemy airplanes would attack London in a raid was still difficult to imagine. Many people thought they were hearing and seeing British planes in the sky. They rushed out of their homes and into the streets to see what was going on.

“The instinctive feeling of the people of London rather seems to be that such attacks are a humiliation, and that they ought not to be possible at all.”

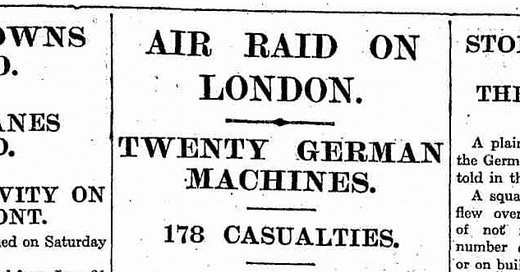

The 14 Gothas (German heavy bombers similar in size and performance to the Handley Page O/400, which I have written about before), flying in tight, organized formation, began dropping dozens of bombs at 11.35 a.m., mainly in the Liverpool Street area. One bomb fell through the roof of a school, killing 18 children. Twenty-five people died in the streets. In all, 162 were killed.

A few kilometres away from all this carnage and destruction was (and still is) one of the most luxurious hotels in London, the Savoy. Opened on the Strand in 1889, by the First World War it was a place crawling with famous actors and actresses, aristocrats, royalty and other glamorous people.

One resident may or may not have been described this way, but he was certainly powerful. Jan Christian Smuts was a South African military leader who would go on to become prime minister of his country after the war. In March of 1917 though, the British prime minister had asked him to come to London and join the Imperial War Cabinet.

Smuts was still in the city, and staying at the Savoy, when the bombs fell on the 13th of June. He would have heard the planes and the bombs themselves exploding. Once the attack was over, he went to the stricken areas to see the damage for himself and talk to people who experienced it first-hand.

What he saw was a population badly shaken. The psychological effects of the raid were clear. People were traumatized by the violent deaths of fellow citizens (including many children), and the damage to buildings. Until now the war may have seemed far away to most Londoners. But the daytime raid showed them that they could be killed in their own homes with little or no warning.

“London might through aerial warfare become part of the battle front”

In the days following, there were the usual platitudes from politicians, the sort of thing we are accustomed to hearing on the news in modern times. The Secretary of State for War told the House of Lords “nothing that we can do will be left undone to guard this country against aircraft invasion.”

Whatever that statement meant, it didn’t amount to much. London was attacked again by German bombers a few weeks later, on the 7th of July. There was apparently less damage this time and fewer deaths, but the psychological damage was at least as great.

The Times newspaper said the feeling among the population was that the raids were insulting. “The instinctive feeling of the people of London rather seems to be that such attacks are a humiliation, and that they ought not to be possible at all.”

London should be untouchable by the enemy, right? How could the planes not have been stopped before they reached the city? The answers were not encouraging. British planes sent to intercept the German attackers were largely ineffective, as were the anti-aircraft guns trying to shoot them down.

At minimum, the Times argued that people should be warned so they could take action to protect themselves. “Every man and woman who wishes to obtain shelter during an air raid should, so far as possible, be given a chance of doing so. A conceivable solution might be the establishment of warning sirens in each borough.”

There were also growing calls for counter-attacks on German territory, both as a way of taking out military capabilities, and in some minds, revenge. Here, the Times peered into the future and saw what was coming. “Aircraft are rapidly becoming a primary means of gaining ultimate victory.”

Four days after the July attack, Smuts handed a report to the British War Cabinet that laid out the stakes of what was going on in a way that no one could ignore. Smuts wrote, “that London might through aerial warfare become part of the battle front.”

Smuts described the British response to the German attack as almost farcical. British pilots had the the latest, most sophisticated airplanes, but they didn’t fly in formation, they communicated poorly, had no coordination, and leadership in the air was weak. Their “guerrilla” attacks had almost no effect.

Then the stakes got even bigger.

When the air raid is on, don’t rush out into the street to watch

By August, the Germans weren’t just attacking London in daylight. Now they were doing it at night too. Suddenly London became a scarier place after dark. The danger on the streets would have been palpable. Lights were dimmed or shut off entirely so as not to help German pilots navigate or see their targets. Police and other authorities would warn people of a coming attack with sirens, or sometimes just shout into the streets.

Coroners inquests held in the days after bombings heard from witnesses who ran into the streets when they heard the planes coming, because they wanted to watch. Others stood at the doorways of their houses and peered out. The results were tragic. One man told an inquest he saw a flash in the air, followed by a tremendous explosion with dense smoke rising from the road. Then he saw a girl and both her parents lying dead in the street.

The coroner concluded that for most people, if they had stayed inside, away from windows and with the doors shut, they may have survived.

Although it’s impossible to escape the feeling that these inquests were blaming victims for their misfortune, it also feels true that finding shelter during an air raid was the only sensible way for people to save their own lives.

Staying indoors was better than standing in the street, but better still was to get underground. There was talk of the need to dig huge holes in parks that people could hide in. But that seemed unnecessary because of the number of basements that existed. Of course, there were also 90 Tube stations around the city.

Air raids only become more frequent

At the end of September, London was attacked by German air raids for four days in a row.

The Times described an unusual stillness that came over the city when raids happened.

“Usually from a height above London one can hear the ceaseless roar of traffic in the streets, the whistles of locomotives, and the noises of motor-vehicles. When the warning was given all these sounds ceased immediately, and after the raid was over they started again, breaking a silence that came rather uncannily in an interval between the firing of the last gun and the issuing of the ‘all clear’ signal.”

Anyone ignoring the warning to take cover would have seen a spectacular show in the air on the evening of Saturday the 29th of September. Defence forces tried to stop the German bombers with a massive barrage of anti-aircraft fire. They used something called star shells. Each had a magnesium flare inside. When fired into the sky, the flare would burn and light up. At times through the evening there were thousands in the air at any given time. The idea was to light up the sky so the German planes could be seen, and shot down.

It didn’t really work. Some were stopped but not all. A group of German bombers got through and struck after 9 p.m., destroying buildings in Notting Hill and other places, as well as damaging Waterloo Station. At least 12 people were killed.

The Tube becomes a sanctuary

During the nights of these bombardments, it’s estimated that as many as 300,000 people were hiding out in the Tube network. Entire families would arrive at a station with bedding, pillows, food, even cherished household items they didn’t want to risk leaving behind.

At Old Street station alone, there were 10,000 on the nights of the raids. Police said the platforms were completely full of people, making it difficult to even get on or off a train. Corridors and stairways were packed too, with barely a single file line allowing people to move.

Underground staff were there and at other Tube stations to try to keep things orderly and safe, but it was probably a tall order. They had to tell people to stay off the tracks and out of the tunnels. Some stations only had a single toilet. The air was described as “foul,” and yet people stayed down there long after authorities told them it was safe to leave.

Many stations had vending machines with snacks in them, but they were usually empty by early evening. “In more than one case,” reported the Times, “an enterprising youth with a view to profit had removed the whole stock, which he sold at a much enhanced price to the people on the platform.”

The future of war is for foreseen

Even before the intense raids of late September, Smuts was convinced of what needed to be done. Around this time a lively debate was happening about air forces. Many thought they should only be used to help achieve the aims of the army or the navy.

But Smuts knew those days were already over. In August he submitted what became a historic report to the British government. In it, he predicted — correctly — how important airplanes and air raids would become. Air forces would now serve their own objectives, not take orders from the army or navy. “Air service on the contrary can be used as an independent means of war operations.”

“There is absolutely no limit to the scale of its future independent war use.”

And then, buried in the middle of a long paragraph in the report, this astonishing sentence:

“And the day may not be far off when aerial operations with their devastation of enemy lands and destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale may become the principal operations of war.”

Smuts wrote this in 1917. Is this not exactly what’s happening in Ukraine in 2022 and 2023? And has happened in countless other conflicts in the 20th and 21st centuries?

The report that Smuts wrote in August, 1917 has been described as the most important document in the history of the creation of the Royal Air Force. The RAF became a reality in 1918, bringing together the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service into a single unit. It was the first independent air force the world had ever seen.

London had been attacked from the air before, but only by Zeppelins. They had bombed the city since the early days of the war, causing damage and killing people. But airships were slow moving, easier to spot, and easier to stop. Airplanes posed a much bigger threat.