The casualty card

The RAF's yellow index cards with flowing handwritten script are the keys that unlock thousands of amazing stories

One of the most fascinating relics of the First World War is the casualty card.

Thousands of these index cards were filled out to keep track of British airmen who suffered some sort of incident — everything from crashing an airplane, to being taken prisoner, to being killed in action.

This is what they looked like.

The above card is for W.E.L. Seward. I wrote a while ago about his adventure off the Mediterranean coast in 1917, when he swam for four hours to escape the enemy. That, for some reason, is not recorded on his casualty card, or it is on another one that I haven’t been able to find. This card shows that he had another incident in September, when his engine failed and he went down with an injury.

I love looking at these cards. Each one is like the storyboard for a movie. Not all the details are there (what injury did Seward suffer?), but there’s enough to construct a scene. It lists the type of plane he was flying (a B.E.2e) and that no one else was on board. It says he went down near the Belah aerodrome in the Middle East. With this information, it’s possible to dive down a rabbit hole and discover much more about Seward, the Middle East campaign, everything.

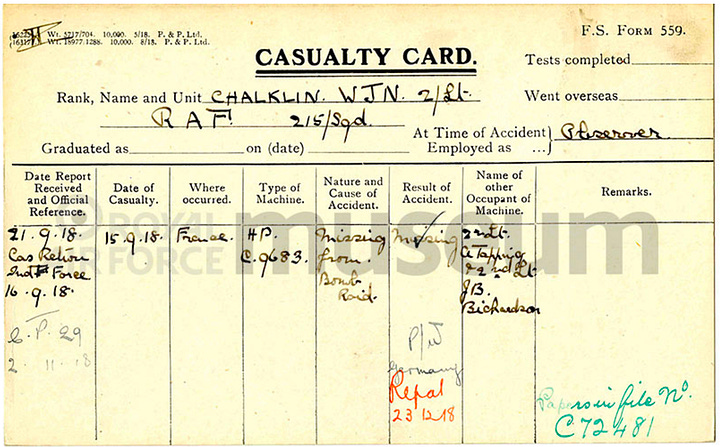

Which is pretty much what happened when I started looking into JBR, my great-grandfather. This is his casualty card.

When I first came across it, I was shocked. I had previously known almost none of this information. It lists the squadron he was with (215), the plane he flew in (H.P. for Handley Page), and the serial number of the plane itself (C9683). It lists the date on which he went missing from the bomb raid, and who his crew mates were (Alfred Tapping and Jack Chalklin). And, spoiler alert, the entry in red ink shows that he was repatriated on 23 December, 1918.

From here, it was easy to find the casualty cards of Tapping and Chalklin.

The information on their cards matches what’s on JBR’s. Much more sleuthing was required to reconstruct the whole picture of what happened to them, but these cards were the keys that unlocked the way in. It would have been far more difficult had these yellow index cards not existed.

The RAF catalogued and organized these cards, bundled them into series (it’s not even well understood why it was done the way it was), and preserved them.

You can see by the water marks that most have been digitized and are available to find via a search. Got a name of someone who flew in the First World War? Feel free to rifle through the card database and see what you can find.

Why do large organizations collect and save so much data? There never seems to be a clear answer to that. These days, social media companies collect data about you so they can sell it and make money.

But the motivation to collect this level of detailed information in the First World War wasn’t as clear. There was an obvious obsession with order and accountability. But maybe the answer was also: just in case we need the info later?

It’s a vague and unconvincing answer, except that it’s completely true. For any of us who want to learn what happened to a person, or what it was like to fly and fight, or pretty much anything else about the war, the cards are the way in.