Prelude to a much longer story about a pilot, and the war

Details emerge about an airman who served in the First World War. It is a myth, a mystery, but also a true story.

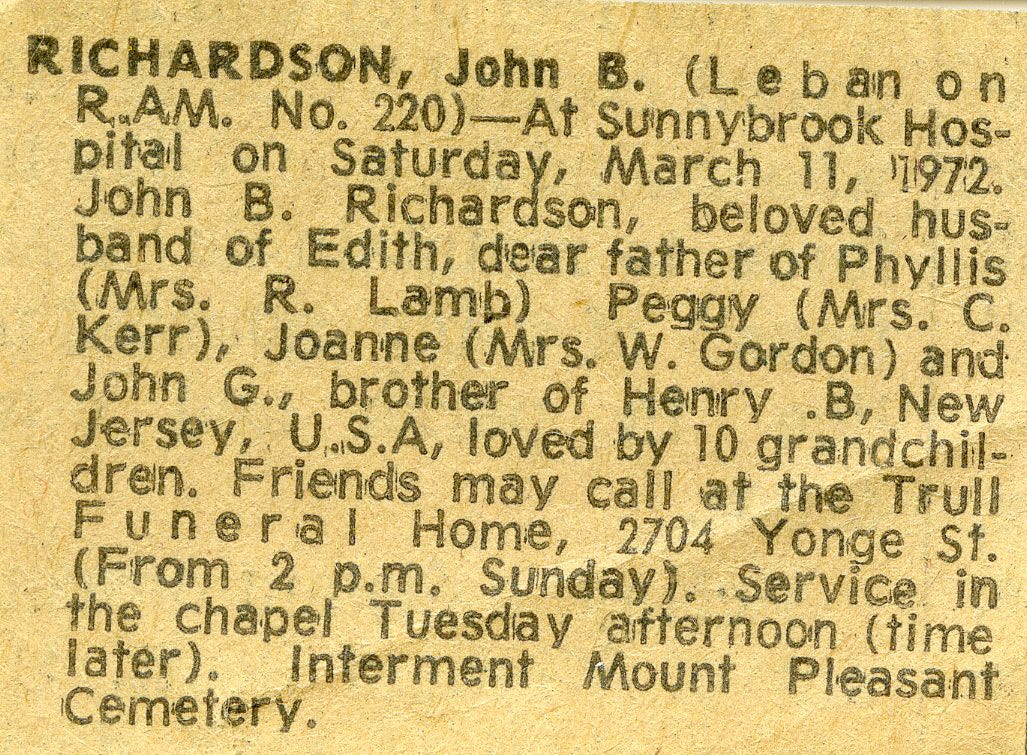

When John Buckland Richardson died at the age of 72 in a hospital bed in Toronto, he was hated by some of his closest family members, and loved by a wide range of friends.

An obituary in the Toronto Star dutifully listed the names of his immediate relations and noted the location of his death, but as was normal for these sorts of newspaper notices, it offered no details on his life.

Richardson’s many friends included pretty much everyone who lived on the lake where he owned a cottage, as well as men he would regularly go hunting with. He was also a member of the Masonic Lodge, and the members held a service for him after he died.

A few days later at the funeral, his wife, children, grandchildren and others were there. But at least some of them may have struggled to express sadness or loss.

To them, he was known for his raging temper, heavy drinking, the physical abuse of his children, intolerance of views he disagreed with, adultery and other forms of dishonesty. His son, also named John, says he doesn’t think anyone shed a tear for the man when the end came.

This was in March of 1972, less than six months before I was born. JBR, as I will call him, was my great-grandfather.

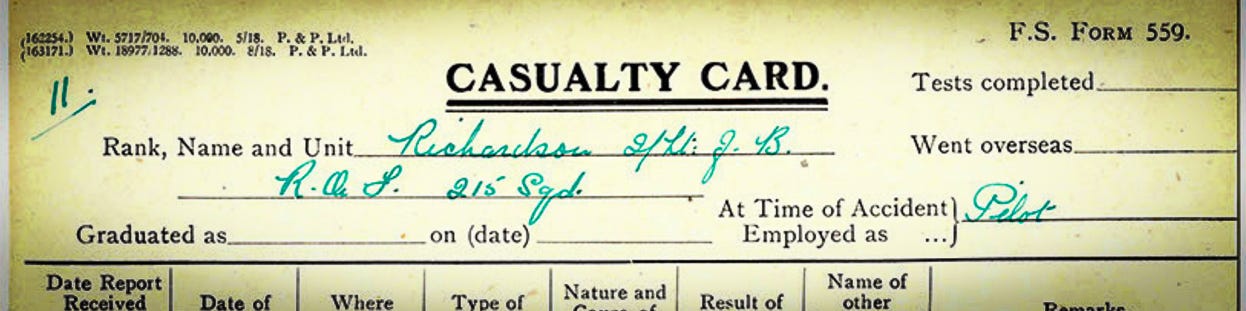

Growing up, I only heard one story about him, which cast him in an entirely different light. I was told he was a pilot in the First World War. He had joined up with the Royal Flying Corps, was shot down over enemy territory and held as a prisoner of war by the Germans. Eventually he was released and went home to London. A few years later he moved to Canada and settled there.

I had seen a photograph, taken during the war, of him in uniform. His cufflinks also survive, and remain in the family as a sort of relic. They are gold, and bear the flag of the RFC (a predecessor to the RAF), light and dark blue bars with a thin red line in the middle. My father is the current custodian of them, and he wears them on special occasions. More than once he has said, “these will be yours one day.”

This was the extent of the story. No one seemed to have much other information. What sort of plane did JBR fly? No one knew. When exactly was he shot down and what were the circumstances? No answers. How did he end up in the air force rather than the infantry, or navy? How many missions did he do? What was it like? Nothing.

The story stood as a myth. It clearly wasn’t made up, but there was so much missing.

More strangely, my grandmother (JBR’s daughter) would downplay his experience whenever she spoke about it. She dismissed his learning to fly as almost prankish behaviour. She said his life as a POW in Germany was one of comfort, not hardship. In the face of what was probably a harrowing tale of flying over enemy territory, surviving a plane crash and being held captive during the bloodiest war in history, she was unimpressed. Her message was clear: others had it worse, so her father’s experience was not worth the attention.

I disagreed. Yes, others definitely had it worse, but JBR’s story struck me as something I wanted to know a lot more about.

Few other details were forthcoming, however, and no other family members I spoke to knew anything else about his wartime experience. It stood as a myth. It clearly wasn’t made up, but there was so much missing. It was calling out to me, but was also elusive and difficult to detect, like an apparition.

The whole thing felt both distant and close at the same time. I never personally knew anyone who fought in the First World War. The oldest people in my life had been children back then. The man at the centre of the story died before I was born. Yet this all felt recent somehow. It was out of reach, but barely.

Stepping into that world, piecing together JBR’s experience, I entered a strange mixture of myth, reality, emotions and ideas that added up to a type of nightmare.

It has been said that the men who flew had it easier than those in the infantry. Flying a plane was better than life in the trenches. Easier, but not easy. Airmen lived under constant mental pressure and stress. They knew their lives could end at any moment, not just from a bullet or a bomb, but due to weather or a failure of the airplane they were barely in control of.

I tried to imagine what it would be like to live like that. Where everything around you is uncertain, and where almost anything can happen at any moment, even things that seem inconceivable. The shattering anxiety of that could cripple almost anyone.

Everything about flying a plane during the First World War was extreme. Airplanes were delicate and known to fall apart or stop working in mid-flight. The science of flight was still poorly understood. Open cockpits left men at the full mercy of cold, thin air. Crews often returned with bullet holes in the aircraft, and even their clothes.

British air forces refused to issue parachutes, because the leadership thought men would jump during flight rather than continue a battle.

Some squadrons flew only at night, which compounded the difficulty of everything else. It was what JBR did, and is a truly terrifying thing to imagine. Navigation was crude. Even in daylight pilots would get lost. At night, landmarks might not be visible at all if lights on the ground were turned off. The darkness could shroud you from anti-aircraft fire, but it was still a threat. Enemy planes could appear at any moment. The weather could change without warning. Amid all this, the job of finding targets and dropping bombs also had to be done.

Most of the targets were military and industrial, but houses were never far away, and were often hit. These men knew they were killing civilians. Dropping bombs from planes at this time was, to say the least, inexact.

There was the fear of being blown out of the sky, which at least offered the chance of a quick death. Being trapped in the cockpit amid flames was a distinct possibility. Pilots were known to carry revolvers so they could finish themselves off rather than burn alive.

Planes were also frequently forced down in enemy territory with everyone surviving. Being captured by local townsfolk? What would they do to someone who had been trying to bomb them?

Those captured and held as prisoners of war entered yet another world of anxiety and fear. Some died waiting for treatment of their wounds. Others escaped, and still others attempted to escape and failed. None of the prisoners knew when or if they would make it home.

This terrifying world was pulling me in, prying my eyes open and forcing me to look. Shouting at me so I couldn’t avoid hearing it. Why was it so insistent? Why was I unable to turn away?

We have to decide whether to explore the past. The door is open, and we can choose to step through. In the case of the First World War, it can be brought alive in astonishing detail. The documentation is so thorough, it feels as though nothing was left unrecorded, unwritten, or unremembered.

This is not true, of course. Much will remain forever unknown. To my surprise, uncovering facts and piecing together details has not really created a fuller picture. It only expands what is unknown, and deepens the myth.

Deciding to look is risky. We don’t know what secrets the past will reveal. Will it haunt me forever? Probably. But to not explore the myth is much worse.